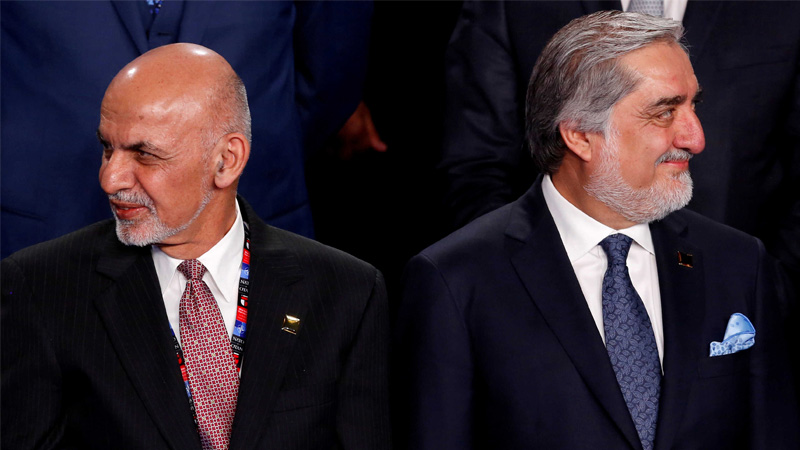

What happens when you run out of leadership? You become a laughingstock and an ever-brawling pack of people. You become clueless of national vision and immerse in conflicting confusions. The Afghan peace process is fast turning into a quagmire of disagreements played out in the clumsy Ghani-Abdullah hands. The regime that was installed and protected by the US is now feeling and seeing the pressure from its erstwhile patron-in-chief, forced to accelerate the peace process thereby settling the inter-political rifts. This comes not in terms of verbal directions but now also in material form as the failed Pompeo visit rings an alarm on funds cuts to the war-torn Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is a complex country timed in the 21st century with the state craft of the 16th century. It is tribal bonds thatjoin the political rank and file in the country with the commonality of religion that binds people further together. The sectarian divide is not polarising as the majority population of more than 80 percent professes the Sunni school of followers, and the two sects recognise mutual restitution from centuries. The spirit of Afghan nationalism overcomes the religious bonds of connectivity.

Afghanistan is a complex country timed in the 21st century with the state craft of the 16th century. It is tribal bonds thatjoin the political rank and file in the country with the commonality of religion that binds people further together. The sectarian divide is not polarising as the majority population of more than 80 percent professes the Sunni school of followers, and the two sects recognise mutual restitution from centuries. The spirit of Afghan nationalism overcomes the religious bonds of connectivity.

The country is composed of more than 20 ethnic groups of which the Pashtun form 42 percent followed by Tajik of around 30 percent.The remaining ethnic groups enjoy a composition less short of two digits. The main political stakeholders are therefore the Pashtun and the Tajik, which are not at daggers drawn. Both cherish the idea of a peaceful and progressive Afghanistan. Patriotism with the motherland of any of the ethnic factions in Afghanistan stands beyond any doubt, but the centre of leadership to attract and influence all under the unionist idea of Afghan nationalism is missing.

After Ahmed Shah Masood, the veteran Afghan leader who put in heroic aggression first against the Soviets and then against the Taliban, the political focus of Afghanistan in terms of vital leadership diluted into tribal groups, clans and major subdivisions. Today, it is the scary want of leadership that is dividing the Afghan political landscape and is giving way to polarised dissent.The responsibility of Afghan peace breakthrough hangs in limbo and unattended.

Whether Ashraf Ghani enjoys the popular Pashtun support or not is in itself a point worth debating. With two percent of turnout and just two million people voting out of 9.7 million registered voters with a total population composition of 35 million, the seat of president as occupied by Ghani raises serious people popularity questions.Acquiring just a little more than 50 percent of the votesthat were castmeans he is the president of 35 million Afghans having won one million votes.

The spirit of Afghan nationalism overcomes the religious bonds of connectivity

The rival claimant Abdullah Abdullah, who has also set up a parallel government, seems to be in much more mercurial state than Ghani. Whether he is famous and acceptable to the Pashtun dominant population of Afghanistan is a matter of complicated concerns. Whether you cast your vote for or against is not as serious a matter as when you decide not to vote. The Pashtun political edge in Afghanistan is an inevitable fact and has a decisive role in breaking or making of stable governments. Mind it, the Taliban factor has dominant proportion composed of Pashtun people too.

It would not be Ghani or Abdullah charisma to unite the Afghan people and hatch organic peace and long-term stability in Afghanistan. The Afghan Taliban are the warring and ostracised faction in Afghanistan, and to meet them in talks would require a cross representative body reflecting and representing the collective Afghan sentiments.The statistics of 2019 Afghan presidential polls deny us the capability of the current government as truly representative of the Afghan people. Therefore, a national jirga would be more effective than the current pony parallel governments in place.

The national jirga is the tribal representation of Afghanistan, which will present the common sentiments of all the ethnic groups in the peace conversation with the Taliban. Things in Afghanistan are still perceived, conceived, transcribed and translated in the utterly tribal ways.The Jirga jargon could be very effective in meeting this national challenge that has cropped up in effect ofthe Doha Peace Accord.

The Afghan peace process is a serious issue, whereas the current Afghan government is anything but serious to accept and settle the challenge. It would be the leftover tribal leaders who have everything at stake to come forth with a peace jirga. Government only needs to provide it the legal cover and patronage. Once the peace talks reach an ultimate juncture, there could be any form of elections to reflect the popular Afghan sentiment and a stable government formation. If the matter is left to the will and wish of the twopresidents, it could fall prey to petty political gains and not reach any material and subjective peace in Afghanistan,which is now tired of mourning its dead and burying its loved ones.

The writer is a civil servant based in Quetta