Recep Tayyip Erdo?an was born on 26 February 1954, 16 years after Ataturk’s death, in Kas?mpa?a, a rough Istanbul neighbourhood. The son of a ferry captain, Erdogan made pocket money by selling Turkish bagels when he wasn’t studying at a religious school. On his way home, as dusk fell in Istanbul, he would use the deck of a cargo ship anchored in the Golden Horn to practise reciting the Koran, earning plaudits for his oratory. But Erdogan also played soccer, dreamed of a career in sports, and rebelled against patriarchy. His fellow Islamists did not approve of his athletic shorts.

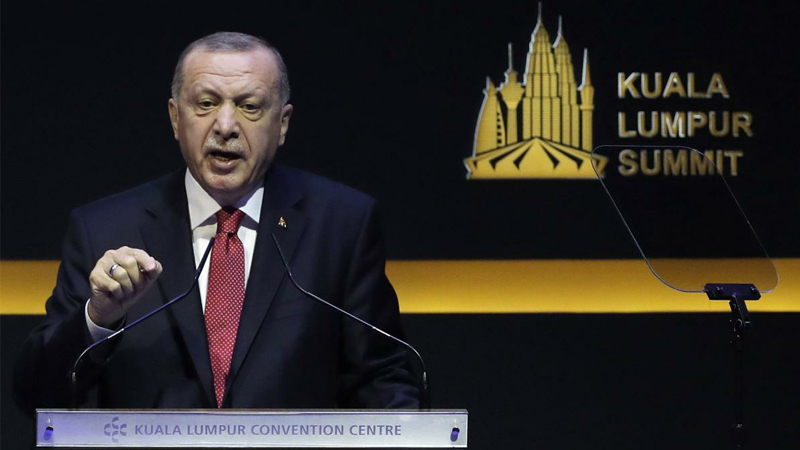

Erdo?an is the 12th and the incumbent president of the Republic of Turkey. He previously served as prime minister of Turkey, from 2003 to 2014, and as mayor of Istanbul, from 1994 to 1998. As his party’s provincial head in Istanbul, Erdogan delivered speeches against “the evil new world order,” protested the Gulf War, and defended the cause of Islamic rebel groups in the Algerian civil war.Erdogan distinguished himself from other Islamists through his calculated pragmatism, ushering in a tectonic shift in Turkish politics over the 1990s. “We don’t need bearded men who are good Koran reciters; we need people who do their job properly,” Erdogan would later say. He founded the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, leading it to election victories in 2002, 2007 and 2011 before standing down upon his election as president in 2014 and in 2018. Coming from an Islamist political background, he has promoted socially conservative and liberal economic policies during his administration.

Erdo?an is the 12th and the incumbent president of the Republic of Turkey. He previously served as prime minister of Turkey, from 2003 to 2014, and as mayor of Istanbul, from 1994 to 1998. As his party’s provincial head in Istanbul, Erdogan delivered speeches against “the evil new world order,” protested the Gulf War, and defended the cause of Islamic rebel groups in the Algerian civil war.Erdogan distinguished himself from other Islamists through his calculated pragmatism, ushering in a tectonic shift in Turkish politics over the 1990s. “We don’t need bearded men who are good Koran reciters; we need people who do their job properly,” Erdogan would later say. He founded the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, leading it to election victories in 2002, 2007 and 2011 before standing down upon his election as president in 2014 and in 2018. Coming from an Islamist political background, he has promoted socially conservative and liberal economic policies during his administration.

The early years of Erdo?an’s tenure as prime minister saw advances in negotiations for Turkey’s membership of the European Union, an economic recovery following a financial crash in 2001, and investments in infrastructure including roads, airports, and a high-speed train network. However, his government remained controversial for its close links with Fethullah Gülen and his Gülen Movement, now designated as a terrorist organisation, with whom the AKP was accused of orchestrating purges against secular bureaucrats and military officers through the Balyoz and Ergenekon trials. In late 2012, his government began peace negotiations with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) to end the ongoing PKK insurgency that began in 1978. The ceasefire broke down in 2015, leading to a renewed escalation in conflict. Erdo?an’s foreign policy has been described as Neo-Ottoman and has involved attempts to prevent Syrian-Kurdish PYD/YPG forces from gaining ground on the Turkish-Syrian border during the Syrian Civil War.

This Turkish leader has, over a period, emerged as one of the strongest and most respected leaders in the Muslim world; he is seen with cynicism and covetousness in the West, and even by other petty rulers serving Western interests in the Muslim world. Erdogan is the most baffling politician to emerge in the 96-year history of Turkey. According to Western analysts,”Erdogan is polarising and popular, autocratic and fatherly, calculating and listless; and is short-tempered: ……but he can also be extremely patient. It has taken him 16 years to forge what he calls “the new Turkey,” an economically self-reliant country with a marginalised opposition and a subservient press.This mix of annoyance and tranquil has made Erdogan progressively more successful at the ballot box.

In 2014, when Erdogan ran for president in order to centralise his authority, more than half of Turks who cast a ballot voted for him. They did so again in 2018, by which time they had also voted to do away with the post of prime minister altogether. Erdogan has converted his popular mandate into power and used that power to remake Turkey’s relations with the rest of the world. He has expanded Turkish influence in Syria and northern Iraq and tilted Turkeytoward China, Iran, Pakistan and Russia despite being the member country of NATO. Erdogan may win a third presidential term in 2023. If that happens, and Erdogan leaves office in 2028, he will go down in history as Turkey’s second-longest-serving president, a year shy of Kemal Ataturk’s rule.

In his political career, Erdogan has also changed his self-presentation over time, from anti-Western Islamist to conservative democrat. To realise its vision of an Islamist movement compatible with the global order, the AKP joined the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, a Europe-wide political party aimed at reforming, rather than rejecting, the EU. Back home, the AKP developed a strategy of forming alliances to control the Turkish state. In exercising his power, Erdogan worked with both competent bureaucrats and Islamists with political aspirations but little technical knowhow. But therein lay a problem. Erdogan had no cadres to fill the state bureaucracy. Competent functionaries mostly belonged to other political camps. Although the Islamist bureaucrats tended to be skilled at providing public health and transportation services, they showed little interest in education, policing, or intelligence work.

And so, Erdogan resurrected the Ottoman tradition of indirect rule. He outsourced different components of the state-the judiciary, the police force, and the military-to different power players. Between 2003 and 2013, the old-school bureaucrats who opposed the AKP’s globalist agenda were replaced in the Foreign Ministry and the judiciary by ambitious new cadres. Most had backgrounds in the network of religious schools run by Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic preacher who has lived in exile in Pennsylvania since 1999, after being accused of seeking to undermine Turkey’s secular order.

This Turkish leader has, over a period, emerged as one of the strongest and most respected leaders in the Muslim world

In foreign policy, another field in which his cadres lacked expertise, Erdogan handed the reins to Ahmet Davutoglu, a scholar of international relations often described as “the Turkish Henry Kissinger,” and named him foreign minister in 2009. The AKP foreign ministers who preceded Davutoglu had preserved Turkey’s Western-focused foreign policy doctrine. As a member of NATO, a US ally, and a candidate for EU membership since 1999, Turkey had kept its distance from China, Iran and Russia. Turkey was the inheritor of the Ottoman caliphate, Davutoglu wrote, and that it needed to move from a “wing state” of the West to a “pivot state.”

Taking advantage of its location at the intersection of the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Europe, Turkey was poised to lead Islamic nations. Erdogan relished these turgid ambitions, and as the Arab Spring unfolded, Turkey set its sights on Syria, where it hoped for a regime change instigated by the Free Syrian Army, and on Egypt, where it placed all its chips on the Muslim Brotherhood. The Davutoglu doctrine allowed Erdogan to reinvent himself as a global Islamic leader, someone who could improve the lot of Muslims not only in Turkey but elsewhere, too. Erdogan successfully overcame Gezi protests and defeated putsch in 2016, overcame numerous economic challenges, foreign policy issues and raised Turkey’s stature among the Muslim countries successfully that has created a lot of abdominal pain in some Western countries and their allies suffering from Islamophobia. Erdogan said after winning a third term as prime minister in 2011, “Believe me, Sarajevo won today as much as Istanbul. Beirut won as much as Izmir. Damascus won as much as Ankara. Ramallah, Nablus, Jenin, the West Bank, Jerusalem won as much as Diyarbakir.” Erdogan’s bold stance and pronouncements about atrocities committed Israel in Gaza, Western Bank against Palestinians, and by state of India in the occupied Kashmir and now against Muslims all over India, speak volumes for his political stature as a strong Muslim leader with highest morals and commitment, disregarding any cost that it might incur.

Recently, as if to assist future biographers, Erdogan periodised his reign. In a television interview, he named his Islamist years, in the Welfare Party and as mayor of Istanbul, as an “apprenticeship.” His time as a reformist prime minister was his “journey-man ship.” But it is his years in the presidency that, in Erdo?an’sview, deserve the privileged title of “mastership.”

In the presidential palace, plasma screens track which news stories are most widely read in the country, requiring specialists to rapidly address the snowballing problems that people care about, but a few dozen officers are hardly sufficient for a nation of 82 million. Despite such challenges, Turkey’s civil society remains strong. Turkey has 52 million active social media users. In recent years, initiatives focusing on the security of ballot counting, fact checking in media, LGBTQ rights, and violence against women have gained traction.

As the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk has noted, “Once a country gets too rich and complex, the leader may think himself to be too powerful, but individuals also feel powerful.” Erdo?an’s great challenge over the next decade, as individualism grows in Turkey and Islamophobic populism rises in Europe, will be to convince voters that his mixture of anger and patience is still a model to follow, that his formation story can continue to inspire, and that only his unassailable ability can steer Turkey to safety. Erdogan will no doubt do everything in his power to succeed at this overwhelming task.

Here in Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan who became prime minister after 22 years of political struggle, promising great changes, faces somewhat similar political, economic and administrative challenges, and has a lot to learn from the political career of Tayyip Erdogan. The most recent visit of Erdogan to Pakistan and signing of dozens of MoUs in important fields have laid the foundation for an ever greater and stronger political, economic and military cooperation between the two brotherly countries that need to be expanded with inclusion of Iran, Azerbaijan, Central Asian Republics and even with China and Russia with or without SCO or CSTO umbrellas.

The writer is a retired senior Army officer with rich experience in International relations, diplomacy and analysis of geo-strategic issues