LACKING VOICE – I

Sanghar/Mirpur khas: It’s mid-afternoon. Haimi’s colourful ghaghra and chuli have turned shabby from dust and sweet absorbed by the fabric all day during her tours of various settlements in the outskirts of Mirpurkhas to beg for food. Her effort has paid off, and she has collected enough food to feed the family.

Once she is back at her slum in the Bheelabad Colony, the family uses the begging bowls to put food and sits down for lunch. Having finished his meals quicker than others, Honio, a male member of this household from the Jandawra gypsy community, moves to a side and starts repairing a stone grinder, a now obsolete device to manually crush wheat grain. The Jandawras have traditionally specialised in making and repairing of stone grinders.

Locally known as Khanabadosh, the gypsy communities are scattered across the country, in slums set up along roadsides and in vacant plots. These slums lack all basic amenities like potable water, sanitation, electricity, and gas.

In Sindh, Gurgula, Baaghri, Saami, Jogi, Jandawra, Gowarya and Shikari are the major gypsy tribes. Kabootra, Oad, and Parkirya Kohli are also found in the province. They associate with different religions, including Islam and Hinduism.

At Haimi’s slum in Bheelabad, a campaign team of the local Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) candidate has hoisted the party’s tri-coloured flag. The PPP’s populist slogan of ‘roti, kapra aur makan’ still resonates with some elders in Bheelabad, but like their fellow gypsies elsewhere in the country, most of the dwellers of the slum will not cast ballots on July 25, since they don’t have a Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC), a mandatory document needed for voting.

It isn’t as if these gypsy families haven’t tried. Haimi says she and her other clan members have made several attempts, paying the registration fees as well. However, each time they were told off on grounds that they lacked required documents.

ADARSH, a Sindh-based non-government organisation that works with gypsy communities, tells Daily Times that the National Database and Registration Authority’s (NADRA) rules make it near impossible for personnel from these communities to get a CNIC.

And recent changes to the rules have made things even more difficult. The new rules require applicants to produce birth certificates, besides getting their applications attested by a family member carrying a CNIC, and, in the case of a married woman, producing the husband’s CNIC.

“Since about 80 percent of the gypsies don’t have CNICs, therefore, their children find it extremely difficult to get theirs,” Aasan, a representative of ADARSH, says.

There is no official record of the country’s gypsy population. However, according to an estimate of GODH, a Lahore-based organisation, the numbers run upwards of 10 million, mostly found in the outskirts major cities and towns.

Social activists believe that while the earlier generations of gypsies remained unaware of the benefits of their IDs, many members of the community are now better aware. They say that in recent years, some NGOs have raised the issue, making gypsies aware of the benefits of their identity documents.

Besides, the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), a federal cash transfer programme started by the PPP government in 2008, and the Wattan Card, launched in 2010 flood relief efforts, has played an important role in motivating gypsies to get their identity documents.

However, to get CNICs, the gypsies require permanent home addresses, meaning that they have to settle down, even if temporarily on state or private land. This is where a large portion of the gypsy families get exploited by influential landlords who let them settle in return for their political loyalty.

The new NADRA rules require applicants to produce birth certificates, besides getting their applications attested by a family member carrying a CNIC, and, in the case of a married woman, producing the husband’s CNIC.

Over a decade ago, Ilyas Sheikh and his family, who belongs to the Shikari gypsy community, had settled at a privately owned land in Sanghar’s Khadro Town.

Shikaris, or hunters, have historically been Hindus but they converted to Islam some generations ago. In Ilyas’s family, male members work as wage laborers in towns, while women work as farm workers.

The elders of the community say that those who possess CNICs and are registered to vote have to follow the directives of their waderas’ – the feudal on whose land the family resides.

“Since our wadera is the owner of the land, we are bound to cast our vote for the candidate he picks. If we don’t obey, he will dislodge us from his land and we will become nomads again,” Ilyas says, adding that if the wadera changes his affiliation with a political party and joins other, the tenants have to follow suit.

Even though the Shikaris have settled down in shanties, they still lack all basic facilities. “There are no latrines here. To answer the call of nature, we have to go to the fields for open defecation. Women suffer the most as their dignity gets compromised,” Illyas says.

In some instances, landlords go to the extent of confiscating the CNICs of the gypsies residing on their lands to ensure that they vote for a candidate of his choice.

Mangha Ram, a social activist, recalls that after the 2013 elections, some members of the Saami community, who had migrated from Thatta to Matiari, contacted him and requested assistance to get new CNICs. “Their cards had been taken away by the feudal on whose land they were living,” he says.

There is another category of gypsies. These aren’t stuck in patronage-based relation with a landlord and can cast ballots. Many in this category have however lost trust in the electoral process in view of ‘broken promises of politicians’.

Banna, 25, is a snake charmer, locally known as jogis. Like his family members, he travels around the year and he earns his livelilood by entertaining people with his snake charming skills. Recently, his clan left Jamshoro and made a month-long stopover in Sanghar. The family chose to reside with a relative who are temporarily settled in a slum at a privately owned land.

Bana says he and most of his other family members carry CNICs and have casted votes in the past. However, in the 2018 elections, Banna has decided to not cast his vote as a protest against ‘the government’s apathy towards the gypsy community’.

“Catching snakes is a dangerous exercise. Often there are casualties and deaths in our clan. No government has done anything to provide us jobs so we have no other option to earn a living,” he says, adding, “Pait k liay kerna perta hai (you have to do it for the earthly needs).

Recalling PPP chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s recent visit to his area during his campaign trail, Banna says many members of the community including women were dancing in a traditional style when the PPP caravan passed in front of their roadside slums.

“The fact of the matter is that neither the PPP nor any other party’s government has done anything for us. Around 40 years ago, his (Bilawal’s) grandfather (former Prime Minister) Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had given land to our elders in Umerkot. A Jogi Colony still exists there,” Banna says.

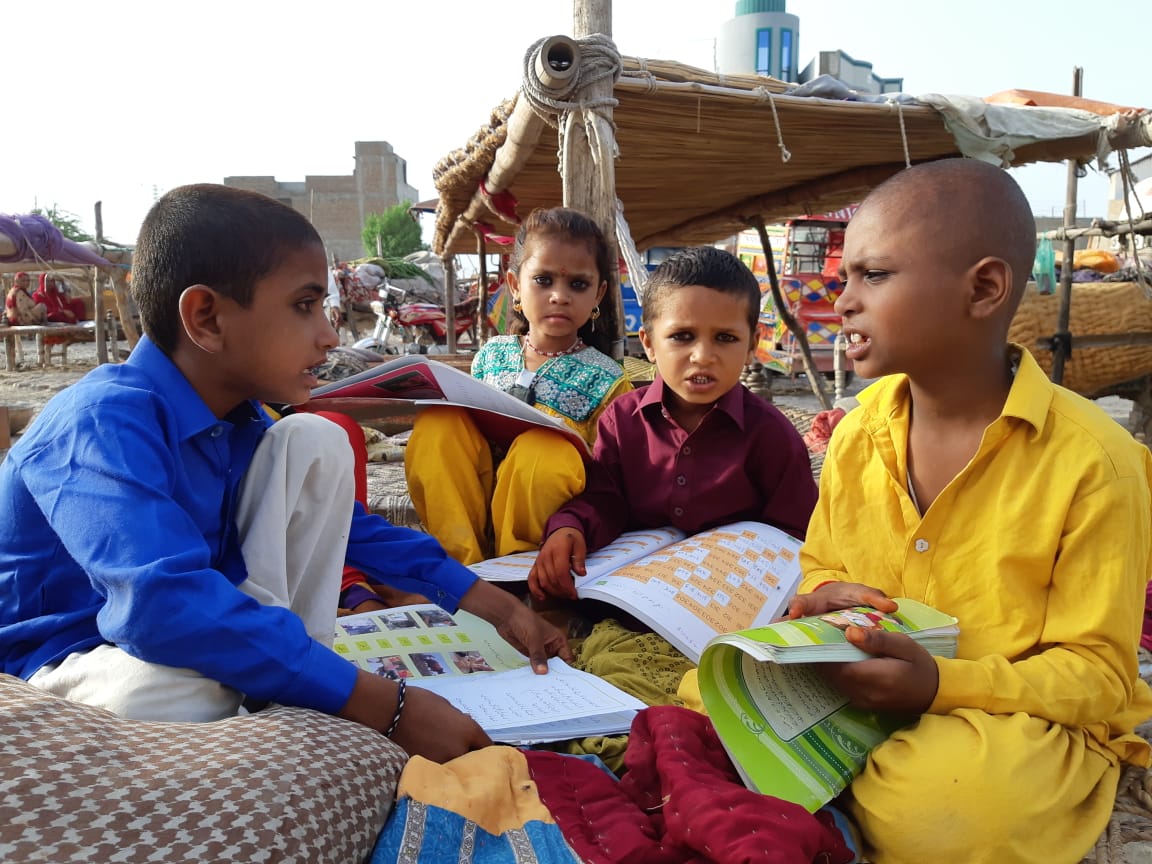

He continues, “when it’s election time, candidates make false promises to take our votes. Public representatives improve their own status but our life remains unchanged. We have no proper arrangements for shelter, jobs, food, water and children’s education. We can’t settle permanently on someone else’s land because they don’t allow that. Our next generations will also be beggars like us. So I have decided that it’s best to not cast my vote at all.”

Abandoned by the state and political and civil society

Pakistan’s census does not collect data on gypsies. The absence of any statistics for the community means that gypsies remain out of the government’s priority list, says Rana Asif, a human rights lawyer.

The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) has also not taken any measure to ensure that all the gypsy population is added to the electoral rolls.”In Pakistan, any government servicemen or prisoner can cast vote through postal vote, however, there is no such rule for mobile population groups including gypsy communities,” says Kanwar Muhammad Dilshad, the former secretary of the ECP.

“Pakistan is a member of the Commonwealth. Other Commonwealth countries use mobile teams to reach voters in far flung areas who cannot reach polling stations on their own. If this method is used, it may increase the gypsies’ turn out,” Dilshad opines.

It isn’t just the state institutions who have ignored this community. Political parties and civil society groups have also not paid much attention to the disenfranchisement of the gypsies.

“No political party has mentioned this segment of the society in their election manifestos even though many parties and candidates rely on them to increase numbers at their rallies,” Asif notes.

The Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) that arranges trainings of different sectors on the importance of the vote and voting procedures admits that it hasn’t paid attention to gypsies so far. “In our training programmes, we have included different neglected segments like transgenders and differently-abled people. We should have included gypsies in the process too,” says Sarwar Bari, the secretary general of FAFEN.

Published in Daily Times, July 18th 2018.