I was tempted to explore the works of Punjabi writers after I came to know that Punjabi language and literature dominated the third day of the Urdu Conference that was held in the first week of December 2019 in Karachi.

I was tempted to explore the works of Punjabi writers after I came to know that Punjabi language and literature dominated the third day of the Urdu Conference that was held in the first week of December 2019 in Karachi.

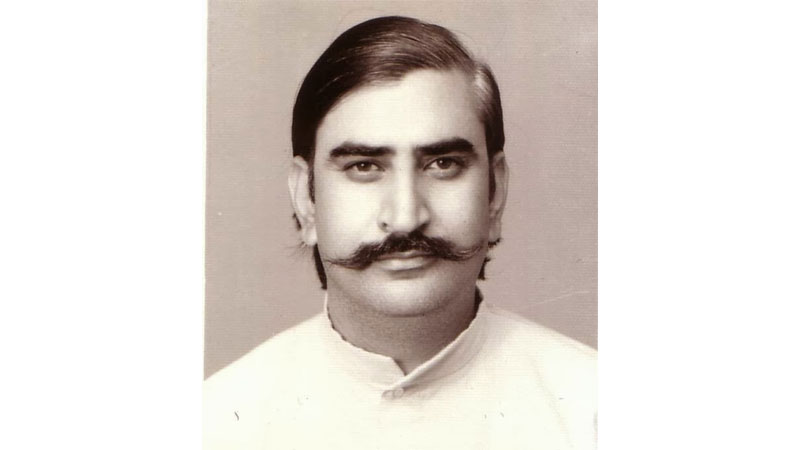

The foremost of the names in Punjabi literature that came to my mind was that of Afzal Hasan Randhawa, known for his outstanding works in Punjabi Fiction, Poetry and Translations. Afzal was born in Amritsar, East Punjab. He was educated in Murray College, Sialkot and then graduated from Punjab University’s Law College. Afzal became a lawyer by profession. This is when another city, Faisalabad entered his life where he started his law practice and was an activist at the same time. He played his due role in Faisalabad Bar politics and used to discuss daily activities with his friends.

His love for Punjabi language and literature was so intense that he started writing fiction and saying poetry in this language despite odds against doing so. He remained steadfast. It is only recently when the activism in support of Punjabi language and literature has gained momentum that Afzal’s contributions in this domain as a mature writer have surfaced again.

River (Darya) and the lands in their vicinities and their impact on environment played its due role. The culture of that area became focus of Afzal’s works, being born in undivided Punjab. He has relived old times, around which his stories revolve. His style, expressions and tonal variations have deeply been appreciated. His first novel was titled ‘Deeva Tei Darya’ (earthen lamp and river) published in 1961.

Cast, creed, law and traditions kill the yearnings of love that grow on various branches of a tree and this is the theme of Randhawa’s novel ‘Deeva Tei Darya’. This novel took readers by storm as he made the village’s bravery, ego, traditions, happiness and sorrows as theme of village life and hence of his novel. Earlier Miraan Bukhsh Minhaas had touched upon this theme in his novel ‘Jutt Di Kartoot’ but only one aspect of village life was taken into consideration. Despite that all characters chosen by Randhawa belong to Sikh religion; similarities of attitudes are seen in the Jutt sect in our part of Punjab. The popularity of this novel can be judged from the fact that it has been published many times; first by Maktaba Punjabi Adab, then by daily ‘Anjaam’ Peshawar, thirdly by Indians and fourthly by Punjab Publishers in August 1971. Randhawa had resisted the offer of some university in Indian Punjab to write another novel on this theme or break the novel into various episodes for television. He did not become victim of this temptation as he desired to maintain the sanctity of his original script intact. He transmitted odour of his soil into his body and thus becoming the mirror of Punjab’ rich culture and traditions. He thus represented whole of Punjab rather than an individual, person, family or a village.

Canadian award winner writer Zahid Hassan has translated this novel into Urdu thereby making it accessible to Urdu readers. Among the contemporary writers, Afzal Hasan Randhawa can safely be singled out in whose writings civilization emerges with complete meanings. Zahid Hassan says that after reading the novel, he took fancy to the romance in the novel. His psychic problems were also deeply immersed with the theme of this novel. He got entangled in its magic completely oblivion of the externalities. That is why he managed to translate this novel. The Randhawas, the Sindhus, Ropu and Shamsheer Singh are metaphors coming out of this culture. Shamsheer falls in love with Ropu, daughter of his enemy Sindhus. He murders his cousin and fiancé Jindu in the process. He runs away with Ropu at the time of her marriage, only to be stopped by his brother Harbajan Singh, who considers every girl of the village as his daughter or sister.

Afzal Hasan Randhawa’s second book was published in 1965; a collection of poetry titled Sheesha Ik Lashkaray Do (One Mirror Two Reflections) followed by a book of short stories titled Runn Talwar Tay Ghora (Lady, Sword and Horse) which was published in 1973. Afzal Randhawa’s six poetry collections, which left a mark on the psyche of the society, included Raat Daay Char Safar (Four Journeys of Night) published in 1975; Punjab Di Var in 1979, his collection of long poems which was banned by the martial law regime of Gen Zia, Mitti Di Mehek (Aroma of soil) in 1983; Piyali Wich Aasmaan (Sky in a Cup) in 1983; and Chhewaan Darya (The Sixth River) in 1997. He translated Achebe’s Things Fall Apart into Punjabi as Tutt Bhaj (1986) and Marquez’s ‘A Chronicle of Death Foretold’ as Maut Da Roznamcha (1993). Altaf Hussain Asad writes on the site Media Coverage on October 2017, that Mustansar Hussain Tarar makes a telling remark about Run Talwar Te Ghora: “The title alludes to the bygone culture of Punjab where women, swords and horses defined all about a Punjabi man”. According to Tarar “Run (Woman) was Punjabi literature, Ghora was his fiction and Talwar his poetry”. Tarar lamented that although people are still writing Punjabi fiction, nobody can claim the same commitment to the language as Randhawa had.

Writer Ahmad Salim knew Randhawa since 1960s. Salim was planning to write his biography and had a long conversation with him two years ago. He needed a few more similar long sittings to finish gathering information for the biography; but because both men had busy schedules, this did not happen.

It was Doaba that influenced Salim so deeply that he terms it as “an encyclopedia of the undivided Punjab”. His novel ‘Doaba’ was published in the literary magazine Punjabi Adab and created quite a stir at the time.

“It was a life-like portrayal of Punjabi culture and I consider it a classic. I wrote a laudatory essay on Doaba and, luckily, Randhawa Saheb liked my essay. I used to visit him often; I would meet him at the courts whenever I was in his city. He may be a lawyer by training but he was an even greater advocate of the cause of Punjabi language and literature,” says Salim. Randhawa authored four novels, the other three being Doaba (1981), Suraj Grehan (1984) and Pundh (2001). His four short story collections are Randhawa Dian Kahanian (1988), Munna Koh Lahore (1989) and Illahi Mohar (2013). Randhawa’s contribution to Punjabi literature also included translation works. He translated two great writers of postcolonial literature, Chinua Achebe and Garcia Marquez into Punjabi.

His love for Punjabi language and literature was so intense that he started writing fiction and poetry in this language despite odds against doing so. He remained steadfast. It is only recently when the activism in support of Punjabi language and literature has gained momentum that Afzal’s contributions in this domain as a mature writer have surfaced again

His family reported on Facebook on September 18, 2017 that their beloved father Muhammad Afzal Ahsan Randhawa (Ex MNA & Writer, Poet) passed away at 1. 17 a. m. His Namaz-e-Janaza was held at 1.30pm at Qaim Sayan Qabarastan, Green View Colony Rajay Wala, Faisalabad

Apart from writing Fiction, Randhawa wrote outstanding poetry. Site Media Coverage reported on October 01, 2017 that with the death of Afzal Ahsan Randhawa, there exists is a colossal loss for Punjabi language and literature. Born a decade before the creation of Pakistan, Randhawa enriched this language with a devotion that is rare to find. Though he became active in bar politics from the very start of his legal career, it was Punjab and Punjabi literature which was his first and last love; this is evident by the fact that he started writing Punjabi fiction and poetry at a time when the language was considered ‘seditious’ by authorities and people who wrote in the language were branded as ‘Indian’ agents. He paid no heed to this perception and firmly espoused the cause of his mother language. Randhawa lost his only son in 2014 followed by his wife’s demise and he was lived alone at his residence near Rajaywala thereafter. He was elected MNA from Faisalabad on PPP ticket awarded to him by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1972 and contributed to framing Pakistan’s constitution in 1973. He was disqualified from taking part in politics for seven years by a court during the martial law regime. During all this time he never stopped writing prose and poetry. Some of his representative couplets of his poetry are: “Takhtaton Sidha Takhte Utte/Kaise Uss Likhvaye Bhaag” (One falls from throne to floor as a part of one’s luck)

“Roop Insaani Dahrey Phirde/Asl Ich Buhte Bande Naag” (one finds snakes in human shapes)

“Sutta Hi Na Howe Jehra/Ohnu Aakh Rehya Ain Jaag” (You are telling the person who does not sleep, to wake up)

Randhawa got appreciated, not only by his readers but by his critics as well as he won many awards, including the Pride of Performance Award in 1996, Masud Khadarposh Award, Pakistan Writers’ Guild Award, and many more by Punjabi organizations in India (an award by Punjabi Sahitya Academy), UK, US and Canada.

In a statement, World Punjabi Congress Chairman Fakhar Zaman said, ”Randhawa was my personal friend and we shared many dreams and ideals. I remember when he was a member of National Assembly on PPP platform; he used to make eloquent speeches in the assembly. His magnum opus, titled Diva Tay Darya set new directions in the fresh sensibility and art of novel writing. His poetry and short stories were equally trend setters and undoubtedly he was one of the very few writers who were equally popular in Pakistan and India. Both of us have spent many days together during Indian visits where I witnessed his popularity. I was personally impressed by his diction, imagery and realism. He did not have arrogance of vocabulary and that is why his writings were equally popular in all social echelons”.

The writer is the recipient of the prestigious Pride of Performance award. He can be reached at doc_amjad@hotmail.com