Bollywood stars like Amitabh Bachchan and Shahrukh Khan may have legendary careers and staggering worldwide fame, but there is good reason why – of all the living actors that could have been the subject of a Bollywood biopic – it’s Sanjay Dutt who emerged as a viable choice for ‘Sanju’.

Bollywood stars like Amitabh Bachchan and Shahrukh Khan may have legendary careers and staggering worldwide fame, but there is good reason why – of all the living actors that could have been the subject of a Bollywood biopic – it’s Sanjay Dutt who emerged as a viable choice for ‘Sanju’.

The son of the iconic ‘Mother India’, actress Nargis and actor/activist/politician Sunil Dutt, Sanjay Dutt’s life includes tragedy, drama, crime and redemption in spades-in short, it’s the stuff movies are made of.

Given Sanjay’s highly publicised missteps, writer-director Rajkumar Hirani and co-writer Abhijat Joshi seem well aware that it would be foolish to unabashedly glorify Bollywood’s “bad boy” in fact, in the very first scene of ‘Sanju’, an incensed Sanjay burns a book by a biographer who likens him to Mahatma Gandhi. Soon afterwards, his wife Manyata assures him that they will find a writer to tell his story honestly. “Bad choices make good stories,” she says, “and you are the king of bad choices.” When biographer Winnie Dias is sceptical to come on board, she is quickly convinced of his commitment to the “truths”-warts and all-when he unflinchingly reveals, in front of Manyata, that the number of women he has bedded hovers at 350, “not counting the Prostitute

It’s a strategic setup, presumably intended to persuade us that despite Sanjay having practically tasked Hirani and Joshi to pen this screenplay, ‘Sanju’ isn’t meant to be a hagiography. But while the film doesn’t hide the turbulent trajectory of Sanjay’s journey, it’s eventually clear that Manyata’s words are the only fleeting sign of acknowledgment that Sanjay bears any real responsibility for it. As he recounts the drug-laced, alcohol-soaked, crime-tainted chapters of his past to Winnie, “Sanju” plays out like a highlight reel of his mistakes, but in a way that places the blame anywhere but on Sanjay himself. As Hirani presents it, Sanjay’s rampant addiction issues were triggered by grief over his mother’s illness and a strained relationship with his father, then fuelled by his duplicitous dealer. The illegal possession of weapons in connection to terrorist activity was the unfortunate result of sketchy advice and self-protection, and his dubious public reputation was the solely the work of the ruthless media.

The justifications are especially disappointing, coming from a filmmaker known for his ability to blend side-splitting comedy and moments of tear-jerking melodrama with straight-shooting commentary; from criticizing the questionable ethics of India’s health care system in his 2003 directorial debut “Munna Bhai M.B.B.S” to taking on the problematic practice of idol worship in 2014’s PK, Hirani has built an exceptionally successful career of exposing institutional injustices and questioning social norms through funny, family-friendly fare.

But both the humour and the critique are too frequently misplaced here. In a dangerous, almost irresponsible choice given current global conversations around sexual harassment, Hirani often makes light of Sanjay’s philandering behaviour; the actor’s admission to the 300-plus sexual partners is met with chuckles from both Manyata and Winnie, and when he casually sleeps with the girlfriend of his best friend Kamlesh, the boys have a laugh over the prospect of Kamlesh doing the same in the future so that they’re “even.” And while the film has a playful, almost forgiving, “Sanju will be Sanju” attitude towards his womanizing ways, it saves its criticism for the press, which, if the film is to be believed, served as the biggest villain in this story for painting Sanjay as a terrorist. There’s even the mention of “fake news” at one point, and if there’s any doubt that the film holds the media responsible for almost all of Sanjay’s woes, it’s dispelled by a concluding musical number in which Kapoor, along with the real-life Dutt, dances to lyrics that slam headline-hungry journalists. Although the critique over sensationalist reports isn’t entirely unfounded, its legitimacy is considerably dampened by the absurdity of the song-not to mention the scantily clad female backup dancers.

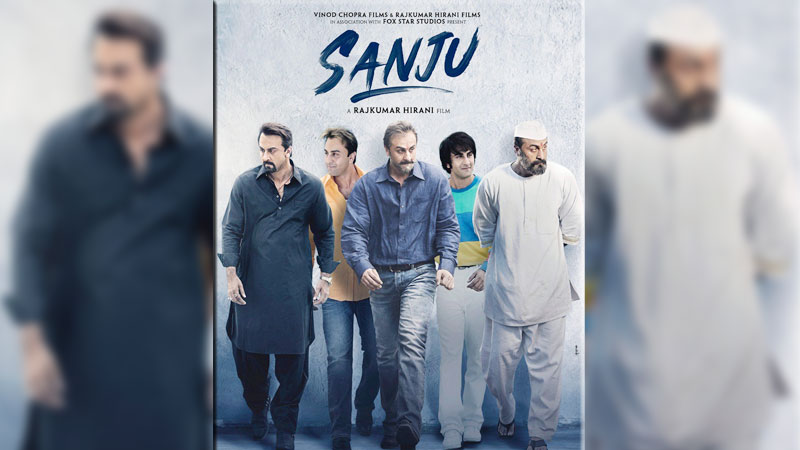

Hirani’s signature quirk simply doesn’t translate well here, and the film’s cartoonish syntax only make the more emotional moments that Sanjay shares with his father or Kamlesh, both of whom serve as moral anchors throughout the narrative, appear confusing at best, melodramatic at worst. But there’s still a beating heart at “Sanju’s core, coming from the central character himself. Mastering Sanjay’s trademark stooped gait, adopting his distinct baritone, with prosthetic hooded eyes, Ranbir Kapoor’s physical transformation is nothing short of astounding, but even more impressive his embodiment of the troubled star’s entitlement, vulnerability, desperation, and despair through the film’s decades-spanning timeline.

While the film has moments that feel farcical, Kapoor steers clear of simplistic mimicry; whether it’s his rock-bottom moments with addiction or an especially heartbreaking scene in a jail cell, he has an ability to hit certain emotional beats well. It’s almost a shame to think about what he could have made of the role, had a stronger screenplay allowed him more of an arc.

Instead, ‘Sanju’ is a reminder that putting a subject on a pedestal isn’t a biopic’s only potential pitfall. Here, it becomes problematic by portraying Sanjay as a victim of his circumstances rather than the master of his own decisions. It may not be gloss over his transgressions, but it makes too many excuses for them, with few lessons learned in the process.

Published in Daily Times, March 23rd 2019.