On the last day of September, India woke up to the disturbing news that authorities had forcibly cremated the body of a 19-year-old Dalit (formerly untouchable) woman who had alleged gang rape and died a day earlier.

On the last day of September, India woke up to the disturbing news that authorities had forcibly cremated the body of a 19-year-old Dalit (formerly untouchable) woman who had alleged gang rape and died a day earlier.

The news caused global outrage, leading to accusations that the young woman – who was allegedly raped by four upper-caste men and had fought for her life for two weeks – was treated as shabbily in death as in life.

The police in Hathras district in Uttar Pradesh state, where the attack took place, said the family had consented to her cremation. But her family and local journalists, who were present in the village when her funeral pyre was lit at around 2:30am, have contested the claim in interviews with the BBC.

“My sister died at 6:55am on Tuesday [29 September] in Delhi’s Safdarjung hospital. Around 9am, they asked us to sign some papers so the body could be taken for a post-mortem,” says the victim’s younger brother. “That was the last time we saw her body,” he adds as we sit chatting on the floor, our backs to the wall in the outer area of his home.

The victim’s brother, his father and two other male relatives had accompanied the victim when she was moved a day before her death to Delhi from the hospital in Aligarh city where she had been treated since 14 September – the day she was attacked.

Hathras superintendent of police Vikrant Vir told BBC last week that the post-mortem was completed by 1pm. “But for some reason her body couldn’t be brought back immediately. It was late night by the time the body arrived in the village. Her father and brother had travelled with the body.”

Last Friday, the state government suspended Mr Vir for “negligence and lax supervision”. Four other policemen were removed too. Calls have also been growing to remove the district magistrate, Mr Laxkar.

While the family was waiting for the body to arrive, police and administration officials had already begun preparations for a late-night funeral. “They had brought in a generator, lights were installed, logs and fuel were brought in,” the teenager’s sister-in-law says.

Journalists present in the village say barricades were erected on the roads leading to the family home and the dirt track that led to a small patch of the field where the funeral was to happen. A white ambulance carrying the body arrived in the village at around midnight. “Besides the driver, there was a policeman and a policewoman in the ambulance. There was no family member in it,” says the victim’s aunt. “It was parked nearby for an hour. We asked them to let us at least see her face,” she tells me, tears streaming down her face.

The black SUV, carrying the victim’s bother and father, reached the village at around 1am and was driven straight to the cremation ground. “Hindus don’t cremate at night,” the brother says. “I told them we can’t have the cremation without rituals and in the absence of our family. When we went home, we heard that the ambulance carrying her body had already arrived in the village.” Officials followed them home and tried to persuade them to go and light the pyre. “The women of the family fell at their feet, begging them to hand over the body so they could perform the rituals. But they were unmoved,” he says. Videos shared widely on news TV channels and social media show the dead woman’s female relatives making several attempts to claim her body. Even though the family had refused to cremate the body, the 19-year-old was still consigned to flames that night.

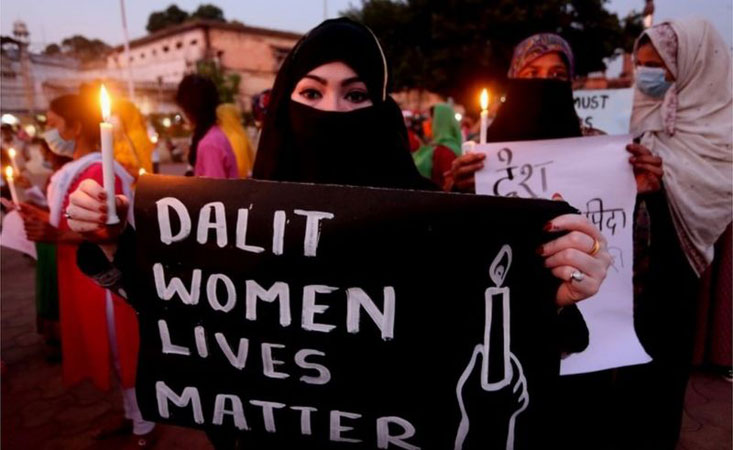

The hasty cremation has caused outrage in India and abroad. Opposition parties have called it “a gross violation of human rights”, “illegal” and “immoral”. Protests have been held across India and by Indians in several American cities. The UN, too, has weighed in, expressing “profound sadness and concern at the continuing cases of sexual violence against women and girls in India”.

On Tuesday, the Uttar Pradesh government told the Supreme Court that they had cremated the body at night due to “extraordinary circumstances and a sequence of unlawful incidents”.

They said there was an “international plot” to cause caste and religious riots in the state and topple the government of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, one of India’s most controversial right-wing politicians. They also claimed that the victim’s family was present for the cremation and had “agreed to attend to avoid further violence”.