It is a sweltering morning of June 1947. Weeks after vicious communal riots in Rawalpindi, Parsis are proffering teary-eyed goodbye to their home, Rawalpindi – standing amid Parsi cemetery on the narrow patches that part each grave, by laying out rose petals with tears rolling down from their faces and saying holy prayers to those who became eternal residents of the city expecting they would never see them again.

Much broken but still strengthened, many left and a few plumped for to stay in the city where they lived and expanded their businesses – Rawalpindi – a city of their dreams.

Today, that place of Parsi heritage is not easily visible in commercial congested areas.

Right in the heart of Rawalpindi, on Murree Road, a hubbub of the city life and noise of traffic, a lane leads to somewhat different place to its surroundings, where a heavy iron gate opens up to an era of Parsi arrival in Rawalpindi – the Parsi burial ground or Parsi cemetery.

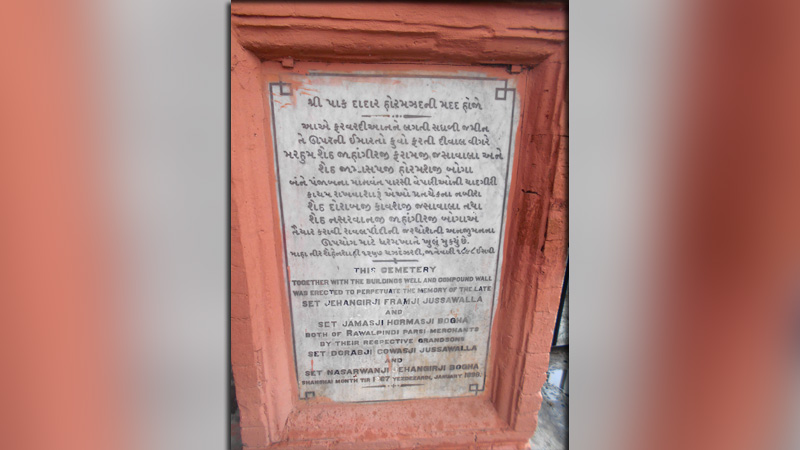

Here, some neighbourhood children play cricket inside the premises and adjoining houses let drainage water on concrete floor of the cemetery making a burbling sound that disturbs tranquility. For new visitors to the cemetery, a marble plaque with bilingual, English and Gujarati inscription, welcomes new visitors, giving answers of basics and sometimes mysteries when people say, “Oh really? We don’t know Parsis bury their dead.”

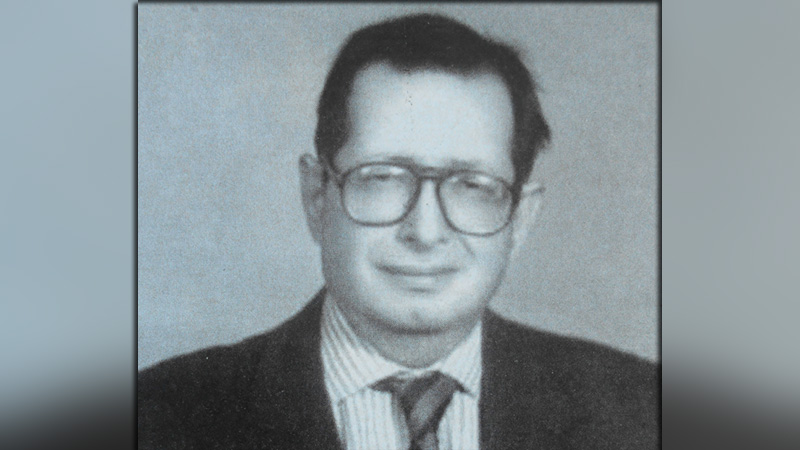

Apart from random travel photographers and some local cricket players, Rawalpindi Parsi Anjuman President and former Member of National Assembly Isphanyar Minocher Bhandara is a regular visitor.

He comes to the cemetery weekly and sometimes twice a week, bringing rose petals, offering prayers on the graves of his beloveds, taking care and fighting illegal encroachments of this religious heritage site.

Here, some neighbourhood children play cricket inside the premises and drainage water spills out on the concrete floor of the cemetery, disturbing the tranquility. For new visitors to the cemetery, a marble plaque with a bilingual inscription welcomes new visitors, giving answers to basic questions and surprising visitors: ‘Oh really? We don’t know Parsis bury their dead’

He’s not only concerned about this site because it’s associated to his own religion but equally concerned about shrinking spaces for Hindus, Kailash, Christians and Buddhists in Pakistan.

He’s a vocal Parsi who stands up for the rights of religious minorities. He goes to Hindu temples, gurdwaras and churches as well. No matter what festival it is, he celebrates Holi, Christmas and Gurpurab with the same enthusiasm.

The Parsi heritage of the city was burgeoned soon after they made Rawalpindi their home that could have been alive however today fuzzy in the mists of time. Talking about the Parsis of Rawalpindi, the most renowned name of them all is that of MP Bhandara, a prolific writer, a columnist and art lover. His real name is Minocher Peshotan Bhandara also known as Minoo.

After a decade past his death, he’s alive in his writings. In the words of Khushwant Singh on the sudden death of Minoo Bhandara, “he was a grievous blow to those who strove to build bridges between Pakistan and India”.

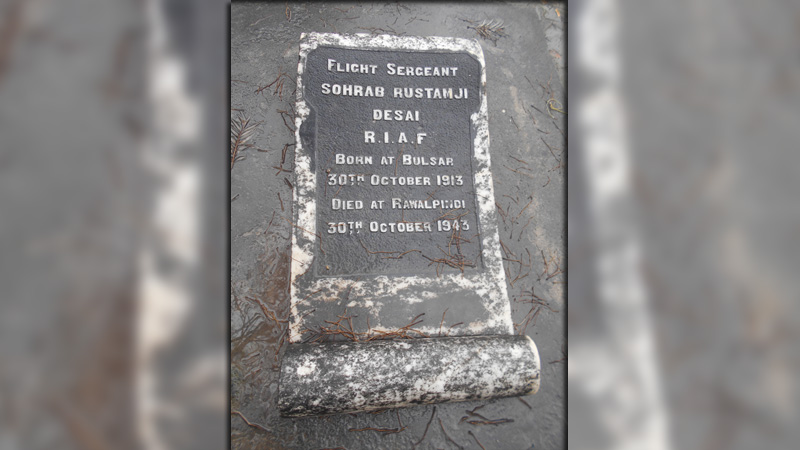

Today, there are around 130 graves in the cemetery, the oldest one dates back to 1860.

The first wave of Parsis came from Gujarat. The inscriptions on tombstones is filled with surnames like Jussawalla and Minwalla. The Walla surname is quite common among Parsis.

Cyrus Broacha, whose family moved from Rawalpindi after Partition, is a well-known anchor and theatre personality based in Mumbai.

Most surnames in the subcontinent reflect caste, lineage and religious beliefs. The Parsis had a delightfully modern streak – having landed without caste, history and context. They created identities through professions and urban streets.

“Our family moved to Bombay from Rawalpindi in 1947. We came as refugees but the family soon settled and by 1953, my father had re-started playing golf at the Willingdon Club. I was eight years old and would walk 18 holes with him every Saturday and Sunday. The three Parsi gentlemen who made up his regular four-ball were uncles Poonawala, Coorlawala and Colabawala. Very soon they had re-christened my father Pindiwala. I used to spend hours searching the telephone directory to find Parsi surnames and stories around their families. There was prohibition in Bombay in those days. So to get liquor, you had to find Dalal, who would introduce you to Daruwala, who in turn would get bottles delivered to your home by Batliwala who would be accompanied by Soda-Water-Bottle-Opener-walla. Other surnames whose ancestors were in the beverages trade were Fountainwala, Ginwala, Rumwala, Sodawala and Jaamwala. Our neighbour and family physician was Dr Adi Doctor – he was only half a doctor. I remember going to Dr Doctor’s sister’s wedding. She married one Mr Screwala. What he did for a living, I don’t know to this day,” Cyrus Broacha says.

In 1898, the grandsons of Jehangirji Framji Jussawalla and Jamasji Hormasji Bogha named Dorabji Cowasji Jussawalla and Nasarwanji Jehangirji Bogha respectively, erected a wall around the burial ground. Jamasji Hormusji Boga aged 72, died on March 21, 1884.

He was at first a priest in Surat and used to convey invitations. Thereafter in 1843, he went to Karachi and spread his business at many places in the name of Jamasji & Sons and settled in Rawalpindi. He left behind a good estate at the time of his death. Dorabji Cowasji Jussawalla donated Rs 500 in 1881 to Bazam for Jashans in memory of his grandfather, late Seth Jehangirji Faramji Jussawalla. Cowasji Jehangirji Jussawalla aged 82 died on December 5, 1900. He joined his family’s well known firm M/s Jehangir Nusserwanji Jussawalla. The branches of this firm were opened in various parts of India. He moved to various branches of the family firm’s shops at Nilgiris, Karachi, Peshawar, Firozpur, and Hyderabad. In 1839, when the British army went to Kabul, at the recommendation of Sir Alexander Burns, his firm opened a shop in Kabul. As the British rule extended in Afghanistan and Peshawar, he took the risk and opened his firm’s shops in Sukkur, Jacobabad, Jalalabad and Kabul. Later, he separated from his family firm and joined as a guarantee broker of Volkart Brothers and Nupni Co. He spent a long time in quietude. He was the father of Seth Cooverji, Nusserwanji, Hormusji, Dorabji, Dadabhai and Jamshedji Cawasji Jussawalla.

There’s a large hall with Roman arched veranda outside the cemetery which accommodates around 200 people, that was built to offer prayers for the deceased.

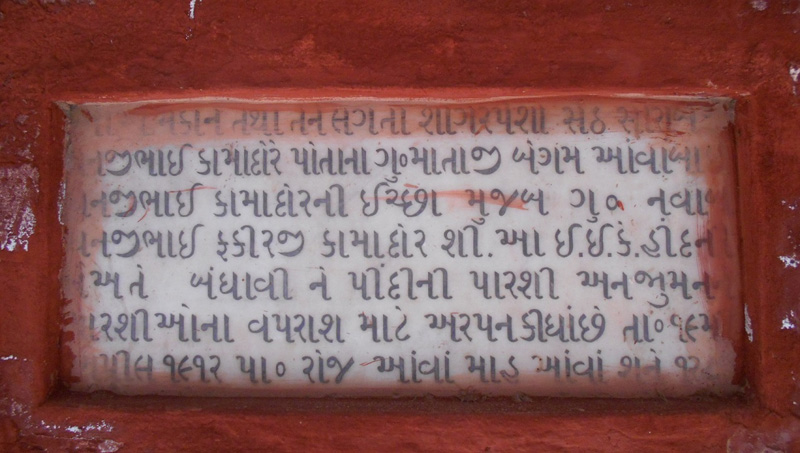

The hall was built by Commodore Fakirji Dhanji Bhouy in the memory of his mother.

This cemetery also serves as a philanthropic work as the well of cemetery is source of drinking water when it becomes scarce in summer, locals throng to get water.

The writer is a freelance journalist, writer and an independent researcher. He is currently documenting Parsi Zoroastrian heritage of Pakistan. He can be reached at rationalist100@gmail.com and Tweets at @OldRwp