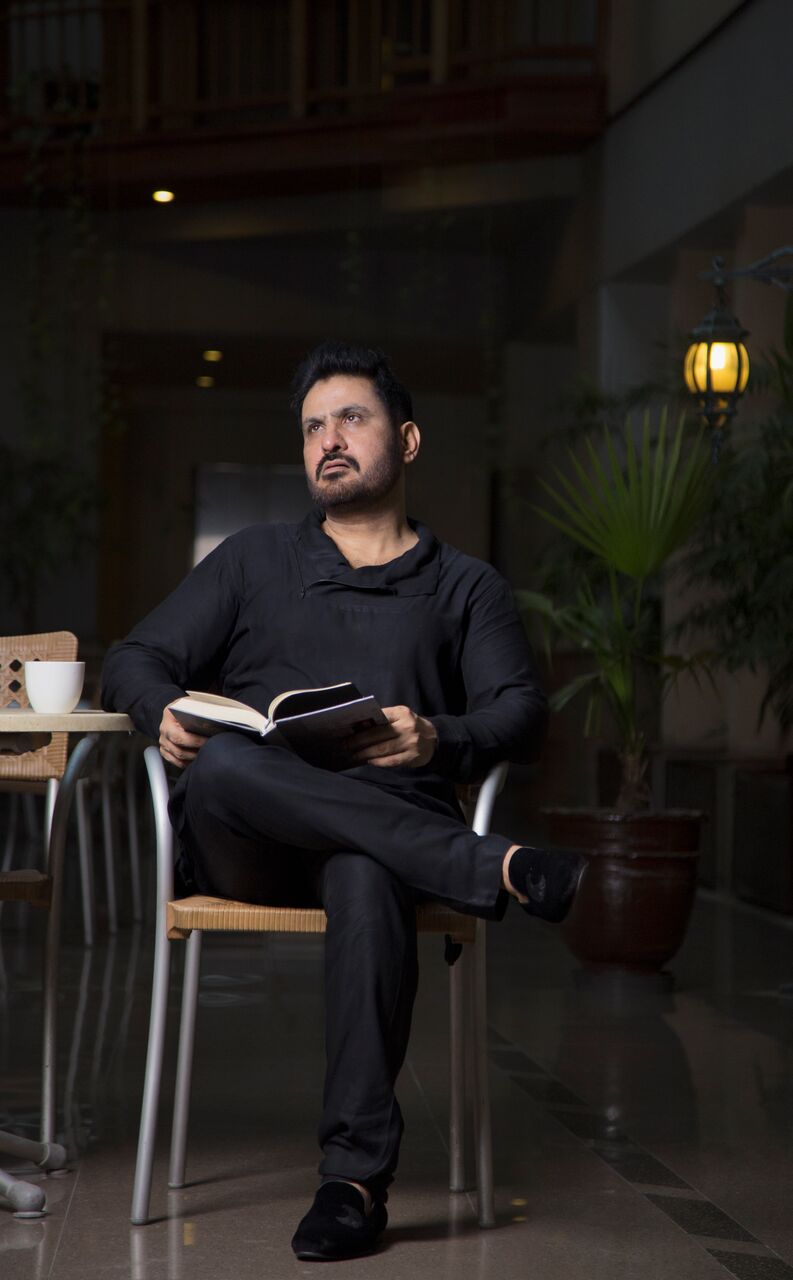

In a career spanning two decades, Faseeh Bari Khan has established himself as one of Pakistan’s most original, brave and talented writers. He has been admired – and reviled – for his bold and brazen portrayal of Pakistani society in serials that include the memorable Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah, Burns Road Ki Nilofer, Khalid Ki Khalda, Mohabbat Jaye Bhar Mein, Khala Kulsum Ka Kumba and Tar-E-Ankaboot. In an exclusive interview for the Daily Times, Faseeh Bari Khan talks to Ally Adnan about his upcoming feature film 7 Din Mohabbat In, life as a writer, nostalgia, cinema, and a lot else.

Your first major feature film, 7 Din Mohabbat In, will be released on Eid-Al-Fitar. Are you excited?

Yes, I am. It feels good to see a project come to fruition.

Are you anxious about the box-office performance of 7 Din Mohabbat In?

I hope and think that 7 Din Mohabbat In will do well at the box-office but am not worried about the commercial success of the film. Success and failure are a part of one’s life. I can deal with both.

What is 7 Din Mohabbat In about?

7 Din Mohabbat In is a comedy that has elements of the sub-genres of character, observational, romantic, and surreal comedy. The characters in the film have been defined with a lot of care and attention. They are funny, interesting and charming. The situations in the film derive humor from the silliness and idiocy of our society and highlight the contradictions that are an intrinsic part of our culture. The dialogs are simple and realistic, written mostly in a deadpan manner. The film has an element of fantasy that is simultaneously bizarre and funny.

7 Din Mohabbat In has been directed by the celebrated duo of Meenu Gaur and Farjad Nabi. How well do you feel the two have interpreted your script?

Meenu and Farjad have done complete justice to my script. The two of them are very talented people with a lot of humility and modesty. They have no issues of ego and work in a friendly manner with an open mind. I enjoyed developing and writing 7 Din Mohabbat In for the duo. We have great chemistry and the channels of communication between us are open and efficient. A number of scenes had to be re-written based on our discussions but that was never a problem because the re-writes, invariably, improved the scenes and because all work was done in a very congenial and pleasant atmosphere.

Your first collaboration with Meenu Gaur and Farjad Nabi, the short film Jeevan Haathi, did not do very well commercially and critically. Do you feel that 7 Din Mohabbat In will fare better than Jeevan Haathi?

I think that 7 Din Mohabbat In will be fare better than Jeevan Haathi because it is a full-fledged feature film whereas the latter was a short film made for television. Jeevan Haathi did not have the scope, budget and scale of a feature film but was released as one. People expected a full-fledged feature film when they went to see Jeevan Haathi and were disappointed by a fifty-minute film made on a modest budget. Jeevan Haathi was marketed incorrectly as a feature film. It did well in festivals, especially in Lahore, Delhi and London, where it was marketed correctly.

What are the strengths of 7 Din Mohabbat In?

The humour of 7 Din Mohabbat In is unique and very different from what has been seen in Pakistani cinema in the past. I think people will enjoy its novelty.

The star power of Mahira Khan and Sheheryar Munawar is a huge strength. They are very popular actors. The play against type in 7 Din Mohabbat In and totally nail the characters of Tipu and Neeli, which are very different from their real-life personae and characters that they have played in the past. Tipu and Neeli belong to interior Karachi and portray the thoughts, sensibilities and beliefs of the class. They talk, act and look like people from the impoverished neighborhoods of Karachi. People will enjoy seeing Mahira Khan and Sheheryar Munawar in the roles of middle class people trying to enjoy life.

The spectacular cast of 7 Din Mohabbat In is another strength of the film. In addition to Mahira Khan and Sheheryar Munawar, it features Hina Dilpazeer, Javed Sheikh, Beo Zafar, Adnan Shah Tipu, Amna Ilyas, Fariha Jabeen, Mira Sethi and many other highly skilled actors.

What is your opinion of the resurgent Pakistani film industry?

I enjoy watching Pakistani films. I think they are good, entertaining and charming.

What new-wave Pakistani films have you enjoyed?

I do not agree with the manner in which the term new-wave is used when classifying Pakistani films made in recent years. The term is often associated with slow, boring films. The truth is that the films being made in Pakistan today are vastly different than the ones that were made in the past. Some of them represent commercial cinema and a few represent art cinema but, together, they constitute new-wave Pakistani cinema.

What do you think of the Pakistani films made in the nineteen sixties and seventies?

I love those films. A lot of good films were made in the nineteen sixties and seventies but those were tough times for cinema in Pakistan. Many daring filmmakers made ground-breaking, experimental films but most, if not all, failed to do well commercially or critically. The situation is better today. We have numerous avenues for showcasing films, access to international markets, world-class theaters, and abundant opportunities to take our films to festivals. This was not the case in the sixties and seventies; had it been so, a number of very good films made by trailblazing filmmakers made would have achieved international renown. Masood Parvez’s Sukh Ka Sapna (1962), Shamim Ashraf Malik’s Ghar Pyara Ghar (1968), Zia Sarhadi’s Shehar Aur Saye (1974), and Javed Jabbar’s Musafir (1976) are a few examples of such films. A number of major literary figures contributed to films at the time. As a result, the stories and dialogs of the film were very good. Anwar Batalavi wrote S. Suleman’s Baji (1963). Suroor Barabankvi’s Aakhri Station (1965) was based on a story by Hajra Masroor. Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi wrote the dialogs for S. Suleman’s Lori (1966). Saadat Hasan Manto’s short stories Mummy and License were adapted for cinema. Filmmakers did not have the opportunities, money and wherewithal that are available today but produced some g films. I genuinely nice films. I love Riza Shahid’s Susral (1962), Jameel Akhtar’s Khamosh Raho (1964), Baby Islam’s Tanha (1964), Attaur Rehman Khan’s Nawab Sirajuddola (1967), and Farid Ahmad’s Bandagi (1972) and Angarey (1972).

You hold a Master’s degree in Urdu Literature. How did your education help you become a writer?

My education helped me develop my intellect, style and imagination. It encouraged me to find and read books that I may not have otherwise studied. A lot of novels and short stories that I read, as a student, captivated me and forced me to want to write. I became a writer because of my education.

But you chose to write for theater, television and cinema and did not write novels and short stories.

Yes, that is true. As a young man, I wanted to write short stories, not dramas and films, but could not deal with the politics and intrigue of the literary world. I sought and found refuge in writing dramas.

A lot of television plays tell stories of either very poor or very rich, people. You, however, almost always write about the petite bourgeoisie. What is the reason behind your fascination with the particular segment of society?

I identify with people who belong to the lower middle classes and am fascinated by their behavior, culture and values. I am unable to write about enormously rich, extremely good-looking people to satisfy the demands of television channels and filmmakers. I can only write about people that I find interesting, real and charming. Those, almost always, are member of the petite bourgeoisie.

What do you think of the class structure of Pakistan?

We are a nation of confused people who are mostly artificial, shallow and superficial. Thanks to these traits, it has become impossibly difficult for talented artists to survive, let alone thrive, in our society. Actors, writers, musicians, and even human beings, who are good, are treated with suspicion, disdain and disrespect. Most of our literati are elitist, insecure and fake. They enjoy asserting their intellectual and cultural credentials by demeaning artists that have real talent and merit. The class structure of Pakistan is based on money, power and social standing. People who do not have these three are treated like lepers.

Your plays have been criticised for being crude, vulgar and tawdry. Do you feel the criticism is warranted?

It is a free world and everyone has a right to their opinion. Therefore, even when it is unwarranted and unfair, one needs to deal with criticism. I largely ignore it.

I write my own stories. They are inhabited by characters that I create. They act in ways that I want them to act. The development of my stories is based on my ideas, thoughts and beliefs. I do not understand why people expect me to write stories based on the desires of others? I cannot and will not write stories to indulge television channel moguls and filmmakers. If they need didactic, synthetically clean, and pretty stories, they need to look elsewhere. My writing will always accurately reflect our society – full of both ugliness and beauty – as I see it.

Why do you think your plays attract severe criticism and censure even when they do well in ratings?

Pakistanis want to listen to the truth and see it, as well, but have trouble facing it. People appreciate the honesty of my plays but are uncomfortable dealing with it. They often tell me that they love my plays but are uncomfortable watching them with members of their families. They find it easy to watch plays like Humsafar, Meri Zaat Zarra-E-Be Nishaan, and Zindagi Gulzar Hai but are uneasy watching Behkawa, Mohabbat Jaye Bhar Mein, and Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah. I understand but do not respect their moral ambivalence and hypocrisy. It does not bother me but is truly sad. I try to be happy with the fact that they acknowledge the honesty and integrity of my plays, even when they find them difficult to watch.

Why was Madam Shabana Aur Baby Rizwana banned?

Madam Shabana Aur Baby Rizwana was banned because it presented the unvarnished, undistorted and brutal truth of our society. The play told the sad story of a prostitute who is unable to make a living selling her body and has to resort to begging on the streets to feed herself. People were unable to accept the hard fact that such women exist in Pakistani society. They are more comfortable with Mirza Hadi Ruswa’s portrayal of prostitutes as a beautiful woman with hearts of gold, bedecked in glittering clothes and jewelry, looking to find solace and redemption in the arms of male saviors. Those prostitutes, alluring though they might be, do not exist in our society. Women like the ones in Madam Shabana Aur Baby Rizwana do. People were unable to handle the truth shown in the play and worked to force it off the air. The ban imposed on the play is still in effect. No one can see the play but I am proud to have written it. In fact, I am proud of all my plays that have been deemed too daring, immoral and vulgar.

How did you feel when the immensely popular Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah was shut down after one hundred and fifty-five highly rated episodes?

I felt very sad when the serial was shut down and was appalled by the manner in which it was forced off the air.

People loved the serial. It ran for a phenomenal one hundred and fifty-five episodes but the custodians of the Pakistani morality had issues with the play. It was too candid and honest for them. A few people claimed that it portrayed Urdu-speaking people negatively. Some felt that it was disrespectful to women. And there were those who felt that it made fun of Biharis. I think that the biggest problem that people had with Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah was the lack of rich, beautiful people in the serial. It was not glamorous enough for viewers used to watching impossibly rich, extremely good-looking and enormously glamorous people on television. The folks at the channel allowed Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah to continue because of its high ratings but treated the serial like a step-child. They kept changing the days and times of airing, ostensibly for no rhyme or reason, and eventually shut it down, giving in to the pressure mounted by the Pakistani moral brigade. I was forced to condense the last eleven (11) episodes into four (4) so that they could get the serial off the air sooner. The channel promised to revive the serial at a later stage. That promise has not been kept.

Hina Dilpazeer famously played twenty-two very robust and intricately written characters in Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah. Which one was your favorite character?

It was Shakooran, the titular widow of Quddisi Sahab. Hers was an unsavory character but had a lot of charm and appeal. Shakooran had a disagreeable but effective manner of getting what she wanted. I loved her machinations and the games that she played. She had a lot of knowledge of old films, poetry and music. Her persona evoked feelings of nostalgia which I found very endearing. Her conversation was peppered with colorful anecdotes and proverbs from Delhi that people – and I – enjoyed a lot.

You pay a lot of attention to the definition and development of the characters in your plays. Why is characterisation so important?

Characterisation is the most important element of writing plays. If a writer defines and develops characters well, they take care of the story on their own. I believe that Quddusi Sahab Ki Bewah lasted for a hundred and fifty-five episodes because of the strength of its characters and could have gone on for hundreds more because the characters of the serial were real, funny and engaging. I am surprised that people tend to place a lot emphasis on stories and largely ignore characters. It is the lack of focus on characterisation that has limited the types of people in our plays to an innocent sister, a loving brother, a cunning mother-in-law and a few others. The same characters appear in all plays, regardless of the story, plot and theme. No one had the desire, ability or willingness to create new characters. That is sad.

A lot of your television plays seem to derive inspiration from Radio Pakistan Karachi’s long-running program Hamid Miyan Ke Haan. Do you feel that Intezar Hussain’s writing influenced your work?

Yes, it has and a great deal. I have never denied the influence and feel great pride in knowing that my work reminds people of Intezar Hussain’s writing.

I was a fan of radio dramas as a child. I used to wait all week for Hamid Miyan Ke Haan and would stay glued to the radio while the play was aired. Listening to the play was a weekly family ritual that all of us enjoyed greatly. We could not imagine Sunday mornings without Hamid Miyan Ke Haan. The series had a number of very interesting characters that had been refined to perfection. The dialogs were simple but effective. The issues presented in Hamid Miyan Ke Haan were ones that we could all relate to. And the humor was smart, intelligent and subtle. I loved Hamid Miyan Ke Haan.

You have written both for television and cinema. How is writing for the two media different?

I find it more difficult to write films, primarily, because it is a very commercial medium and one has to always keep the box-office in mind while writing. Compared to television, the pressure to write something that will succeed commercially is much higher in cinema.

I have established myself as a writer of merit on television and, therefore, do not have to deal with a lot of interference when writing plays. On the other hand, I am new to cinema and have to incorporate suggestions from producers and directors into my scripts. This was disconcerting at first but I have since become comfortable with the collaborative manner in which writing is done for cinema.

Your work celebrates nostalgia unabashedly. Do you feel that the past was much better than the present?

I am an incurable romantic and a very sentimental person. I thrive on nostalgia. And, yes, I do think that the past was much better than the present. The Karachi that I grew up in was very different from today’s Karachi. It was vastly superior in every possible way. People were more cultured in the past. They had a genuine love for the arts. They were liberal, tolerant and open-minded. They knew how to appreciate love, beauty and art. They operated from a morally and ethically sound set of values. I miss those people.

What is your fondest childhood memory?

I think it is one of going to cinemas. Films used to visually opulent, emotionally rich, and intellectually resonant, when I was a child. They were more appealing aesthetically. They had a lot of glamour. Watching films was glamorous in itself. The movie houses of the nineteen sixties and seventies were nothing like the multiplexes we have today. They were huge, stunning and dazzling. People used to dress up to go to Karachi’s cinemas. Men dressed up in suits, wearing neckties, and women wearing saris, sporting brooches – one would see people treating going to the cinema like a celebration of sorts. The discordant but alluring smells of cinema – cologne, food and a lot else – and the accompanying sounds haunt my memories. I belong to the past. I wish I could relive the times.

Mazhar Moin has directed almost all of your television plays in the past. What is the source of the great chemistry that the two of you have with each other?

I think it is the great interest that the two of us have in people. We like to observe and study the behavior, values and characters of people. We find their idiosyncrasies, eccentricities and peculiarities interesting. We enjoy watching people act in strange, sometimes silly, way. We develop characters in our plays based on our observations. We have long discussions about characters over tea at all sorts of places, at all sorts of hours. We like to create intricate characters that are realistic and interesting. I think it is our commitment to characterization that binds us together. It certainly brings out the best in us. I do not think I can ever have the chemistry that I have with Mazhar Moin with any other director.

Ali Tahir is directing your upcoming television serial, Mohini Mansion Ki Cinderella. How does it feel to be working with someone other than Mazhar Moin?

Ali Tahir is a very capable and intelligent director. I am enjoying working with him.

Hina Dilpazeer has been the star of most of your plays. Why does she not have a part in Mohini Mansion Ki Cinderellaein?

Mohini Mansion Ki Cinderella in is the story of a die-hard fan of Shabnam, the superstar from yesteryear who reigned Pakistani film industry for three decades. I had written the serial with Hina Dilpazeer in mind but she was unable to give us the dates that we needed for shooting due to conflicting commitments. This was terribly disappointing for me but Ali Tahir stepped in and suggested that we cast the real-life Shabnam in the role that I had written for Hina Dilapzeer. I loved his suggestion and was very happy – and grateful – when he got Shabnam to sign on to do the serial.

You like to work with a specific and rather small set of people. Are Sheheryar Munawar and Mahira Khan, the stars of 7 Din Mohabbat In, now a part of the set?

Sheheryar Munawar and Mahira Khan are genuinely nice people with pure souls and hearts. They are humble, down-to-earth and kind. When they were cast in 7 Din Mohabbat In, a lot of people said that they would not be able to do justice to the characters of Tipu and Neeli but I ignored the comments, chalking them up to mischief-making. My belief was that Sheheryar and Mahira are superstars who will bring people to the theaters and thorough professionals who will work hard to play their parts well. They lived up to my expectations. I am glad that the two actors play the leads in 7 Din Mohabbat In and hope to work with them again in the future.

The writer lives in Dallas and writes about culture, history and the arts. He tweets @allyadnan and can be reached at allyadnan@outlook.com