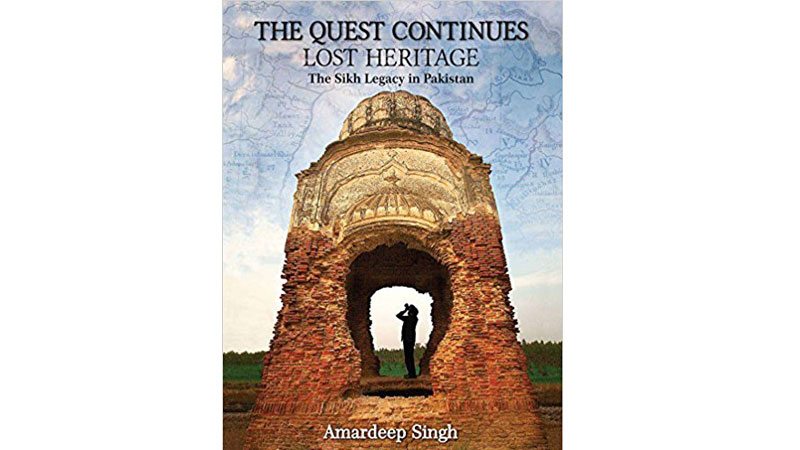

The Quest Continues: Lost Heritage — The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan

Author: Amardeep Singh

Publishers: Himalayan Books, New Delhi

Edition: 2018

The Times of 25 December 2015 published under the title, ‘A heritage all but erased’ a review I did of Amardeep Singh’s first book, Lost Heritage; The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan. In his debut work he had published stunning photographs of Sikhs gurdwaras, shrines, mansions and a variety of other relics left behind in what became the Pakistani Punjab after the partition of mid-August 1947.

Towards the end of his first book he had made a profoundly moving remark after visiting his parents’ hometown, Muzaffarabad, Azad Kashmir, that finally he had achieved the closure needed to overcome the trauma and pain he had inherited from his parents and family and indeed the Sikh community whose ancestral abodes where left behind in Pakistan.

His new book, however, is a continuation along the same path. It seems that either that closure he proclaimed then was premature or, perhaps, that trauma and pain has metamorphosed into a deeper curiosity, deriving from a combination of emotions and intellectual concerns, to continue delving into the Sikh connection to Pakistan.

This time the journey began from very close — just 1.5 kilometres from the international border laid down by the Radcliffe Award with a visit to Rori Sahib Gurdwara. It is now in a dilapidated state. It is now a cowshed. He then visited some other gurdwaras and historical sites of Sikhs before returning to Lahore.

From Lahore he travelled to Islamabad. Thus, began a journey starting in Islamabad-Rawalpindi and as far as the Khyber Pass on the Afghan border. We also learn that syncretic saints continue to be held in veneration. For example, at Kot Fateh Khan in Fateh Jang Tehsil, he saw a gurdwara still standing known as the Baba Than Singh Gurdwara. Although the Hindus and Sikhs of that village and neighboring areas are all gone Baba Than Singh continues to be venerated by the Muslims. He is now addressed as Sultan Than Singh. The appellate Baba has been erased wherever the text from the past is in Urdu and instead Sultan has been inserted. After every Friday prayers the villagers light up lamps and candles And yet Singh continues to be used in the end. The common belief prevails that anyone who tries to damage the building will suffer and folklore is full of examples from the past and present of vandals been punished.

When he visited Sikh sites in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and the Northern Areas including Skardu he found an abandoned gurdwara. Hindus and Sikhs dispersed in small communities all over. He learnt that the Hindus and Sikhs living there were attacked very soon after the coalition government in the Punjab led by Sir Khizr Hayat Khan Tiwana fell when Khizr resigned on 2 March 1947. By 11 March 1947 all of them had left for safe havens. In Swat and other such places Hindus and Sikhs survive and the Hindus tend to perform their religious rites in Sikh gurdwaras or in shared places of the two communities. Understandably he makes a strong point of the Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh inflicting defeat on the Afghans and extending his empire into the northern regions of Pakistan. He proudly asserts that it was Maharaja Ranjit Singh who after a thousand years drove the Afghans out of Punjab and extended his kingdom into Pakhtun territory.

After his journey in the north he then travelled southwards visiting the southern districts of Punjab and then crossing over to Sindh. In Sindh he travelled far and wide. The interesting fact about Sindh is that the Sindhi Hindus are Nanakpanthis, that is, followers of Guru Nanak. That is another form of confluence which syncretism has taken. That is interesting because only after the partition of India and Punjab did Hinduism and Sikhism become distinctly different and separate religious communities. It coincided with the leadership passing from the hands of Khatris of western Punjab into the hands of Jatts of East Punjab.

This time the book contains greater commentary on the partition and how it happened. Overall, while extolling the contribution of Sikhs and deploring the bad state in which their sites are in Pakistan Amardeep pays glowing tributes to Pakistanis from all sections of society receiving him warmly and helping him. On the other hand, the book also brings forth the tragedy of the partition. Their religious, spiritual and temporal sites in Pakistan suffer from neglect. Understandably with the Sikh community now gone such a thing was bound to happen. The Pakistan Government does maintain some important shrines and gurdwaras in good shape, but it is not possible for it to look after all that was left behind in 1947

To have undertaken a journey from one end of Pakistan to the other and in the process captured hundreds of paintings and architectural remnants of Sikhs on camera makes the new book a very worthy complementary contribution to his first book. Amardeep is a genius of a photographer. Nothing registers so easily and moves people so readily than pictures, still and moving.

Perhaps a Punjabi Muslim whose family belonged to the other side of pre-partition Punjab should undertake a journey to East Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh and tell the story of the Muslim heritage left behind there. And, hopefully a Punjabi Hindu would one day come to Pakistan and record the Hindu heritage left behind. The trauma of partition hit Punjabi Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs most and therefore they can through pictorial books can tell a fuller story of the Punjab: connecting the last 70 years to its historical past. Amardeep Singh has shown the way how one can do it and do it well.

The writer is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Stockholm University; Visiting Professor Government College University; and, Honorary Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. He has written a number of books and won many awards, he can be reached on billumian@gmail.com

Published in Daily Times, March 9th 2018.