How have your international performances shaped your music career?

How have your international performances shaped your music career?

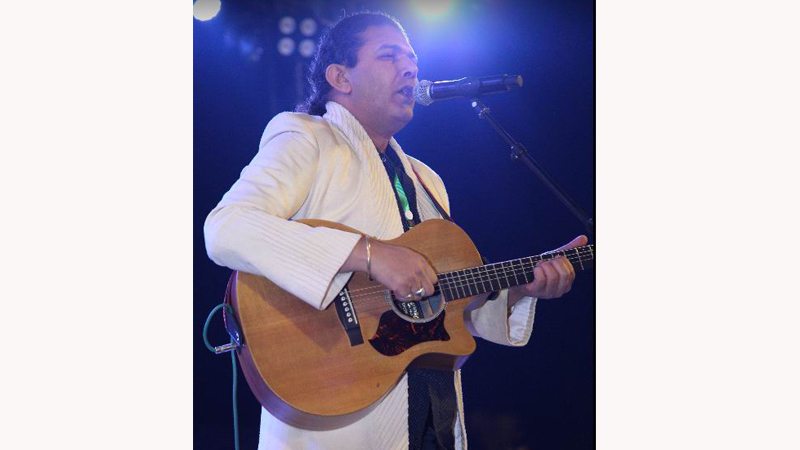

From the age of 19 to 32, I lived in Croatia. Though I had previous experience of performing at left wing political gatherings in Karachi, it was in Croatia I got into music professionally – first by busking on the streets, then performing at music festivals. However, I had grown up on the folk music of Pakistan, while in Croatia I mostly performed Irish folk music with my popular band ‘Shamrock Rovers’. The experience of performing in all kinds of settings for diverse audiences shaped my musical style enormously and taught me to connect and interpret my music for assorted audiences while giving me an international experience, rather than a localized perspective on the music industry. Today I am aware that many ‘musical formulas’ used to produce Pakistani music catering to domestic audiences do not necessarily translate for a global audience. I try to make music that can speak to people regardless of their national, cultural or religious backgrounds.

You are a journalist, musician, theatrical actor, producer, host and a voice over artist. What is the secret behind you being able to accomplish so much?

First, I am a musician. It is an activity that provides me with ultimate satisfaction. Though I grew up acting in the celebrated Dastak Theatre Group of Karachi founded by Sania Saeed’s father, Mansoor Saeed and my father, Aslam Azhar, I never performed in another play since the age of 19. Therefore, I am a bit rusty in this regard. I like to write and would like to see myself more disciplined in writing, whether it is writing songs, thoughts, poetry or stories. Since I was brought up by my parents to appreciate arts, develop an aesthetic sense as well as empathise with the sufferings of the world and because of the cross-cultural trajectory of my life, it was natural that I should start expressing myself artistically and not remain content with my accomplishments.

The more I learned, the more I became aware of the limits of my knowledge and, therefore, I continue to learn and express myself through art. I produced a 13-episode music travel documentary series in Croatia and Bosnia for a private music channel of Pakistan about eight years ago, and last year, I produced a full-length documentary about the endangered musical instruments of Pakistan titled ‘Indus Blues’ in collaboration with Bipolar films, FACE and USAID. I guess I often find myself in situations where I am able to connect the threads, help friends along the way and create projects that must be finished. If I do not do them, who will?

Tell us how you learned singing, and who were your first mentors?

I was exposed to great music ever since I was in my mother’s belly; my parents used to have an old record player and a fabulous collection of Eastern and Western classical, folk and jazz music. Because my father played a pioneering role in establishing PTV and was involved in promoting classical and folk music on the new medium, many of the great masters of Pakistani music visited our house, and some of my earliest memories are listening to Shaukat Ali, Tufayl Niazi and Reshma. Later, I got into Pathaney Khan, the Qawwali of Sabri Brothers, Nusrat Fateh Ali and Abida Parveen. I consider all of them as my mentors since I was definitely influenced by them. Growing up I also fell in love with the music of Victor Jara, the great poet and musician of Chile. During my stay in Croatia I delved into Irish music and was greatly influenced by Christy Moore, the Bothy Band and other Irish folk bands. The music of the Balkans also heavily influenced me, particularly Roma Gypsy music and Bosnian and Macedonian folk.

Though I took a number of classes of Opera singing from an old master in Zagreb, it was only when I returned to Pakistan that I started studying our Folk and Classical music and began sitting with the Ustads. I am still learning Classical music from Azam Bakshi Sahib and Bakshi Salamat Qawwali Gharana. I also constantly learn a lot from my band mates, master of flute Akmal Qadri, Kashif Ali Dani (table player) and guitarist Zeeshan Mansoor of Malang Party.

A defining moment in my career was when Rohail Hyatt called me to perform at Coke Studio Season 2, and my music immediately became known to a much wider audience. Performing regularly at the Rafi Peer festivals and sharing the stage with the best folk musicians of the country also made me more confident about my work. Internationally, it was our month long Center Stage 2012 tour of the USA that was so significant, since we had never before been on the road together for so long as a band and got the opportunity to present our music to foreign audiences, many of which had never been heard before music from Pakistan.

As the founder of Music Mela Festival and Art Langar Festival, Islamabad, what has been your inspiration behind pursuing such artistic pursuits?

I had never planned to become a festival organizer. Of course, I am connected with musicians across Pakistan and abroad. I have also performed at and attended festivals in other parts of the world, in particular the InMusic festival of Zagreb, organised by a friend who I also used to work with. Upon returning to Pakistan in 2003, I observed that there were hardly any platforms for performing artists in our country and that anyone who was able to help in building these platforms should do so! Together with friends, I got involved in promoting the underground scene of Islamabad through various jam sessions we used to call ‘Sweet Leaf City Jams’. When the US embassy approached me in 2013 and expressed their interest in organising a music conference, I thought that for the same budget, it would be better to organise a music festival with conferences on the sidelines and thus the Music Mela was born. I teamed up with FACE foundation and curated the Music Mela festivals for three consecutive years.

Last year, I decided to expand my vision and established the Art Langar festival. Music Mela had already inspired festivals in other cities. I aspired to create a Music and Arts festival to encompass the spirit of charity. The idea was to preserve cultures and develop a philosophy based on human values. By incorporating ‘Langar’ or the idea of a soup kitchen for street children and orphans, I also wanted to emphasize that ‘food for the soul’ is as important as ‘food for the body’, if we are to fulfill our potential as human beings.

Sufi poetry has its own essence and persona. What aspects of Sufi poetry are close to your heart?

All the aspects of Sufi Poetry stem from the root philosophy of Wahdat-ul-Wujood or ‘Unity of Being’, which says that everything is a reflection of the same. The way towards establishing a connection with this truth is to love all of creation and not to let lesser desires of ego dominate you. While emphasising a connection with the spirit of divine love, all Sufi poets have also been critical of the hypocrisies of those who use religion to justify their own selfish inclinations. In this regard, Bulleh Shah and Sachal Sarmast were perhaps the most outspoken in their critique, which makes their poetry all the more relevant today, where we see more people using religion to divide rather than unify humanity.

In your opinion, how much has Pakistan’s pop music evolved during the first boom it experienced during the 80s-90s when Vital Signs, Junoon, Fringe Benefits and Awaz emerged on the scene?

When mentioning Pakistan’s pop music history, one often tends to forget the pre-Zia era of Pakistan when many rock and pop bands, comprising musicians from mostly the Christian community used to perform at several nightclubs of Pakistan. When the state policy of ‘Islamisation’ was instituted by General Zia, all music venues were shut down. Some of the notable exceptions that continued their careers for a few more years were Alamgir, Benjamin Sisters, Muhammad Ali Shehki and later, the magical duo Nazia and Zohaib. The pop music scene then experienced a rebirth when the first democratically elected government of Benazir Bhutto came to power in the late 80s and it continued to grow through the Musharraf era, which saw the maximum number of music TV channels and LIVE concerts. With the onslaught of terrorism, public concerts no longer were a reality and all music channels were forced to go off air. This was the state of affairs when Coke Studio appeared with a great platform for fusing folk music with pop and rock music. However, I believe that the music industry will grow again once public concerts are held. Now with a growing trend of live music festivals, new life has been breathed into the industry, though it is still difficult for the vast majority of musicians to earn their livelihood.

If your intentions in creating music are pure and you are proactive in your endeavors, then your music will surely find a way to express itself. Among the shortage of creative public spaces and platforms, you must keep creating your own space. Make full use of the internet but never neglect live performances. Find your audiences to take your music to, and keep playing your music for the people. When in doubt, increase the dose!

The writer is a columnist and author and can be reached at omariftikhar@hotmail.com

Published in Daily Times, January 19th 2018.