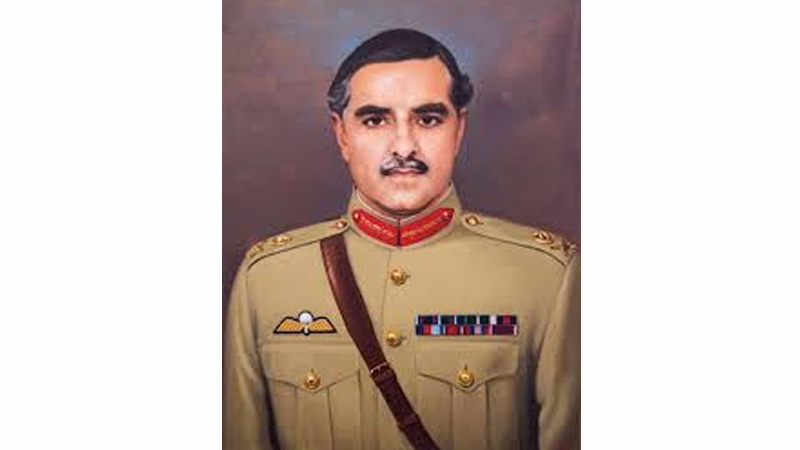

Most books about the army focus on its interference in politics or on its battles with India. Almost none discuss its wartime decision making. General Gul Hassan’s memoirs are the exception. His 30-year career in the army culminated in his becoming the commander-in-chief (C-in-C). And, as he reminds us in the sub-title of the book, he was the last C-in-C. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto replaced the C-in-C position with Chief of Army Staff in the vain hope that it would diminish the risks of an army take over. Gul Hassan began his career in the British Indian Army and went on to serve as aide-de-camp to General (later Field Marshal) Slim. When Pakistan became independent, he became aide-de-camp to Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In his army career, he worked closely with three C-in-C’s, Field Marshal Ayub, General Muhammad Musa and General Yahya Khan, and with de-facto fourth C-in-C, General Hamid. Gul Hassan was the director of military operations during the 1965 war and the chief of general staff during the 1971 war. In between he commanded the first armored division, the army’s premier formation, based in Multan.

Most books about the army focus on its interference in politics or on its battles with India. Almost none discuss its wartime decision making. General Gul Hassan’s memoirs are the exception. His 30-year career in the army culminated in his becoming the commander-in-chief (C-in-C). And, as he reminds us in the sub-title of the book, he was the last C-in-C. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto replaced the C-in-C position with Chief of Army Staff in the vain hope that it would diminish the risks of an army take over. Gul Hassan began his career in the British Indian Army and went on to serve as aide-de-camp to General (later Field Marshal) Slim. When Pakistan became independent, he became aide-de-camp to Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In his army career, he worked closely with three C-in-C’s, Field Marshal Ayub, General Muhammad Musa and General Yahya Khan, and with de-facto fourth C-in-C, General Hamid. Gul Hassan was the director of military operations during the 1965 war and the chief of general staff during the 1971 war. In between he commanded the first armored division, the army’s premier formation, based in Multan.

Gul Hassan says that by September ‘India’s intervention was a foregone conclusion.’ Yayha had reached out to the US and gotten nothing in return. The Chinese had told him to find a political solution. He was now praying that Pakistan would be rescued by angles

Thus, Gul Hassan did not just see history in the making. He was part of history. In the ensuring two decades, he reflected on the great calamity of 1971 in which Pakistan lost half the country and its respect in the community of nations. He was in a good position to comment on decision making within the army’s high command. In 1993 he published his memoir. It came to a devastating conclusion: in 1971, there was a total and inexcusable breakdown in communications between the armed forces that were supposed to fight a war and the high command that had arrogated to itself the task of running the country. The disaster that came could have been prevented. The problem was that General Yahya wore three hats. He was the president, the chief martial law administrator, and the C-in-C. He had no time for running the army since he was busy holding general elections and managing the subsequent tension between the leaders of the majority party which was based entirely in the east and the minority party which was based entirely in the west. Yahya lost his grip on events when he launched Operation Searchlight in the east. Instead of restoring law and order, it gave birth to an interminable insurgency. He appointed Vice Admiral Ahsan as the governor. But Yahya found that Ahsan, despite being given “clear-cut instructions,” was “behaving like a dove in his dealings with Sheikh Mujib. He panicked and lost control.” Yahya relieved him. Next, Yahya appointed Lt.-Gen. Yaqub Khanas the governor and martial law administrator. Based on his assessment of the situation, Yaqub invited Yahya to engage in a dialogue with the Sheikh. When Yahya refused, Yaqub resigned. Much later, Yahya appointed a Bengali civilian governor to stem the tide. But “the change caused no excitement. Then, in quick succession, amnesty for the rebels was announced. This did not elicit even a lukewarm response.” Finally, by-elections were held but they turned out to be “a complete farce” since the candidateswere nominated by the martial law authorities.

Theysoon found themselves on the rebel “hit list.” General Hamid was the chief of staff (CoS). In that role, he was the de facto C-in-C since General Yahya was the president. However, he failed to function as the C-in-C, nor did he carry out his duties as CoS. Says Gul Hassan, Hamid “had found himself in an enviable position where he had all the authority but did not exercise it because he did not want to shoulder the responsibility.” Hamid was the only link GHQ had with the government but he did not share vital information with GHQ. For example, GHQ did not know what was happening on the diplomatic front or what was being planned on the western border with India. In the east, Hamid placed his protégé, Lt.-Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, in command, overlooking his “utter ineptitude.” And when the latter’s failures became too visible to ignore, Hamid “increased his support for Niazi.” Gul Hassan says that by September “India’s intervention was a foregone conclusion.”Yayha had reached out to the US and gotten nothing in return. The Chinese had told him to find a political solution. He was now praying that that Pakistan would be rescued by angles. And Niazi was oblivious to the ground realities. He did not expect an Indian invasion. His troop deployments were designed to prevent India from creating a minor encroachment to set up a puppet government, not to forestall the coordinated, full-scale assault that came in December. The intelligence system had broken down totally since most of the officers were Bengali. At the same time, the martial law authorities had been unable to resolve the problem politically. As the end approached, Niazi seemed to be living in a fool’s paradise and kept on sending “everything is normal” dispatches to GHQ.

Theysoon found themselves on the rebel “hit list.” General Hamid was the chief of staff (CoS). In that role, he was the de facto C-in-C since General Yahya was the president. However, he failed to function as the C-in-C, nor did he carry out his duties as CoS. Says Gul Hassan, Hamid “had found himself in an enviable position where he had all the authority but did not exercise it because he did not want to shoulder the responsibility.” Hamid was the only link GHQ had with the government but he did not share vital information with GHQ. For example, GHQ did not know what was happening on the diplomatic front or what was being planned on the western border with India. In the east, Hamid placed his protégé, Lt.-Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, in command, overlooking his “utter ineptitude.” And when the latter’s failures became too visible to ignore, Hamid “increased his support for Niazi.” Gul Hassan says that by September “India’s intervention was a foregone conclusion.”Yayha had reached out to the US and gotten nothing in return. The Chinese had told him to find a political solution. He was now praying that that Pakistan would be rescued by angles. And Niazi was oblivious to the ground realities. He did not expect an Indian invasion. His troop deployments were designed to prevent India from creating a minor encroachment to set up a puppet government, not to forestall the coordinated, full-scale assault that came in December. The intelligence system had broken down totally since most of the officers were Bengali. At the same time, the martial law authorities had been unable to resolve the problem politically. As the end approached, Niazi seemed to be living in a fool’s paradise and kept on sending “everything is normal” dispatches to GHQ.

After the war ended, Yahya blamed the loss of East Pakistan on ‘the treachery of the Indians.’ Gul Hassan blamed it “on our own blunders.”

Gul Hassan visited the east and apprised Hamid of what he saw. Hamid said he was going to find a way out of the “maelstrom” but did not lay out a plan. Perhaps he was “swayed by General Niazi’s ingeniously contrived reports.” Hamid did not convey Gul Hassan’s assessment to the president. Until the very end, the president remained blind to the conflict between his political and military aims. Gul Hassan noted that one did not need to be a genius “to sense the impending catastrophe.”The army would be fighting the Indians in the front and the rebels on the flanks and in the rear. He said it would be hard to imagine “a more hopelessly disadvantaged position for opposing a superior foe.” And given the circumstances, when he was most needed, the supreme commander, General Yahya Khan, had morphed into “a remote figure.” In the enveloping darkness, there was a complete “absence of direction” and no “cohesion in the nerve-center of the army.” After the war ended, Yahya blamed the loss of East Pakistan on “the treachery of the Indians.” Gul Hassan blamed it “on our own blunders.”

I had first read the memoirssoon after they came out and found them to be rich with tactical details of the two major wars with India. On my second reading, I discovered that they were equally rich on strategy and decision making within the high-command. Unfortunately there are no references orfootnotes in the text. But that is not a fatal flaw, just a limitation common to most memoirs.

I had first read the memoirssoon after they came out and found them to be rich with tactical details of the two major wars with India. On my second reading, I discovered that they were equally rich on strategy and decision making within the high-command. Unfortunately there are no references orfootnotes in the text. But that is not a fatal flaw, just a limitation common to most memoirs.

Published in Daily Times, September 10th 2018.