A highly successful barrister in his early forties – known for his icy and incisive demeamour and having a dashingly impressive personality – was making waves in the political and social circles of the Bombay high society. The tall, lean and slightly greying Mr Jinnah did not so much owe his success at the bar to his immaculate manners, smartly cut suits or his chiseled features than to his toil for two decades to earn the kind of respect and following he commanded in the whole of British India. Till the arrival of MK Gandhi from South Africa, Jinnah was considered the undisputed, emerging leader of the future that many Indian and British notables foresaw as someone who would potentially rule India after the demand for Home Rule had been acceded to by the British empire.

A highly successful barrister in his early forties – known for his icy and incisive demeamour and having a dashingly impressive personality – was making waves in the political and social circles of the Bombay high society. The tall, lean and slightly greying Mr Jinnah did not so much owe his success at the bar to his immaculate manners, smartly cut suits or his chiseled features than to his toil for two decades to earn the kind of respect and following he commanded in the whole of British India. Till the arrival of MK Gandhi from South Africa, Jinnah was considered the undisputed, emerging leader of the future that many Indian and British notables foresaw as someone who would potentially rule India after the demand for Home Rule had been acceded to by the British empire.

Despite his self-enforced celibacy, his hard work and determination to achieve the highest objective chosen in life, Mr Jinnah had not lost his personal charm and attraction towards the opposite gender. But his marriage to an 18-year-old Ruttie Dinshaw Petit would send shock waves in the otherwise steady and tranquil shores of the Bombay elite’s veritable island. Tongues had started to wag not so much for the 24 years age gap between the bride and the groom but for the fact that, despite the homogeneity on the surface, inter faith marriages were still taboo even amongst the well-heeled in the pre-World War I British India.

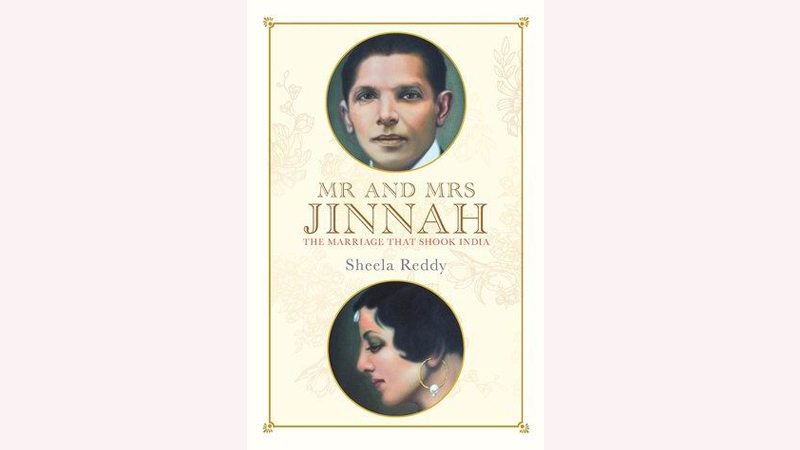

Sheela Reddy’s well researched book recreates those times in a thoroughly enjoyable if not, at times, scintillating, manner; the book like a number of recent books written by Indian authors shows Mr Jinnah in a relatively positive light breaking from the past practice of demonising a very significant, history making character of the pre-partition political history of India.

The fast-moving plot reads like a Victorian novel with the story line circling around an elopement of a vivacious teenager, daughter of a wealthy baronet, with a strikingly good looking middle-aged lawyer who happens to be a good friend of the Parsi baronet. The dramatis personae in the book are some of the familiar historical characters who in the then political landscape were well known household names; Sarojini Naidu, her daughters, Padmaja and Leilamani, Kanji Dwarkadas, Fatima Jinnah, Motilal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi figure recurringly to name but a few.

Jinnah’s marriage to an 18-year-old Ruttie Dinshaw Petit would send shock waves in the otherwise steady and tranquil shores of the Bombay elite’s veritable island. Tongues had started to wag not so much for the 24 years age gap between the bride and the groom but for the fact that, despite the homogeneity on the surface, inter faith marriages were still taboo even amongst the well-heeled in India

With some welcome help from Gandhi, Motilal Nehru had successfully weaned his older daughter Vijay Lakshmi ‘Nan’ away from the dapper, Cambridge educated Muslim journalist, Syud Hossain after Nan had fallen for him. Gandhi requiring Nan to attend his ashram had not appealed to her a single bit. The exercise to change her mind in the name of pseudo-religiosity seemed discriminatory and hence a farce to Nan especially when her Western upbringing had taught her otherwise. Surprisingly, the more liberal and westernised community of Parsis had reacted very sharply to Ruttie’s conversion to Islam, on the other hand. Sir Dinshaw, fresh from losing a legal battle to have Jinnah declared an abductor of his daughter, was under tremendous pressure from his own community to disown his daughter or face excommunication by the Parsi Panchayat.

The early days of marital bliss and the palpable exhilaration of Ruttie while attending political gatherings along with her husband carried on for a few years while the guilt of betraying her parents kept pricking Ruttie’s conscience innocuously but steadily in the background. In the early days of their marriage, apart from the whole Parsi community of India which stood united in fierce opposition to Jinnah, a big majority of upper class households wanted to invite the most talked about couple to their ornate and palatial houses including those of Rajas and Maharajas of India. Raja Sahib of Mahmoodabad and members of his family were so awestruck to see the stunning couple in their house in Lucknow that Ruttie, having been used to dealing with adoring young cousins, had to pick up the Raja’s 4-year-old son to break the awkward and stony silence that hung uncomfortably in the air for a few minutes. Raja Amer Ahmad Khan, the 4-year-old who would refuse to come down from her lap, recounted how he still remembered the fragrance and beauty of that elegant and graceful lady. Sheela Reddy recreates those moments masterfully in her book.

Although there was that magnetic pull between Ruttie the fragile beauty and the charming and strikingly handsome Jinnah which brought them closer initially, the latter’s inability to give enough time and attention to his doting wife meant cracks had started to appear quite early on in the relationship. It was Ruttie’s quality of standing up to people and having an opinion and expressing it despite all odds which attracted him to her. After the wedding was over, MA Jinnah (‘J’ as his young wife had chosen to call him) had immediately got back to his routine of his legal practice during the day and quietly and thoroughly reading the newspapers after dinner almost daily or inviting over his young admirers to discuss politics. Legend has it that even in elaborate dinners and parties which had plenty of occasion for music and dance, the Bombay lawyer would be seen in a dark corner discussing politics with some like-minded guests!

Reddy devotes a full chapter to Ruttie’s struggles to have her husband’s attention which she was finding such an uphill task considering that her dour sister-in-law, Fatima, had started to spend Sundays at the South Court after having been initially bundled off to live with her sister. Ruttie had even yelled at Fatima once, upon seeing her reading the Quran regularly, “the Quran is a book to be talked about not to be read!” Fati’s enrolment in a dental college in Calcutta had seemingly restored Ruttie’s control at home but no development could bring them closer again, her friends were slowly finding out to their anguish. They invariably saw their ‘so lovely and so young’ friend having to deal with ‘life always passing her by leaving her with empty hands and heart’. Depression in the young and idle was not something even doctors in India were trained to treat which meant Ruttie’s hidden conflict between the desire to be independent and duty to be by Jinnah’s side continued.

The arrival of a baby girl had not made an iota of difference to Ruttie’s persona whom she left to the nannies and ayahs to be fed and clothed. Sarojini Naidu was appalled to find out that Ruttie had not named the baby even after a few months of its birth, describing it as ‘a terrified little pet’ without the care of a mother. Ruttie’s ills kept multiplying with her unannounced travels to Europe making her husband worried and exasperated once even compelling him to confide to a friend, “she was a child, I shouldn’t have married her. It was my mistake”.

Veronal, a recently introduced barbiturate was being prescribed indiscriminately by physicians all over the world in those days which was what Ruttie had also started taking for her insomnia. It would be another half a century later that the world knew about the lethal side effects of the drug including the risks of addiction and requiring ever higher dosage to counteract its wearing effect, with overdose leading to death in many cases. It would be fair to say that for a young woman already hopelessly grappling with the frigid withdrawal of her husband, Ruttie’s addiction to increasingly higher dosage of Veronal had sucked the will to live out of her. She took an overdose on her 29th birthday on 20th February 1929, Kanji Dwarkadas disclosed to a Pakistani journalist in 1968, a revelation which had remained a mystery for almost four decades.

The book ends with a couple of devastating sentences echoing MC Chagla, his law office associate:

“….Jinnah wept when he saw the refugees in the country he had just created almost single-handedly. But the tears were less for the refugees than for what he had just done – destroyed yet again that which he loved the most”.

The writer is a Lahore based lawyer. Follow him on twitter @Tariq_Bashir

Published in Daily Times, February 24th 2018.