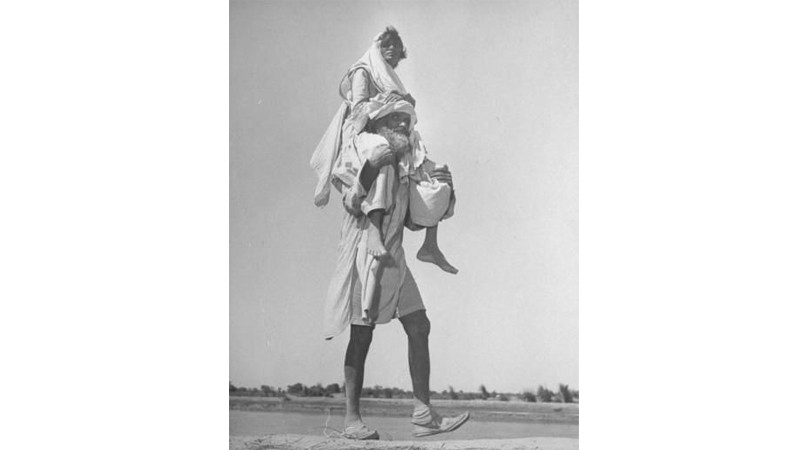

Are there any photos of the Indian partition that stand out in your memory? An elderly woman being carried by a Sikh man on his shoulders? The young boy sitting on a hill near a refugee camp with his head in his hands? Or a heap of bodies near a train?

All these iconic images were photographed by Margarete Bourke-White, an American photojournalist for the Life magazine, who risked her life to bring forth the most intimate peek into the summer of 1947.

Margaret as a photojournalist was more remarkable as she was a woman. Born at the start of the 20th century, Bourke-White lived decades before the era of sexual revolution and feminism, yet made the heroic choices even modern women would be reluctant to make, particularly in a conflict zone.

Bourke-White lived decades before the era of sexual revolution and feminism, yet made the heroic choices even modern women would be reluctant to make, particularly in a conflict zone

Her love for the camera developed when she was a young girl and was supported by her father who was a Jewish engineer from Poland. She started her higher education at Columbia University and studied amphibians as a Zoologist. She left Zoology (unsurprisingly) after her father’s death and eventually did her Bachelors in Arts from Cornell. She left her photographic study of the rural campus and her dormitory, Risley Hall. She moved to Cleveland in Ohio to study commercial photography. This is when she married and two years later, divorced Everett Chapman. In 1927, Margrate White adopted her mother’s Bourke surname as her middle name and hyphenated it.

Her first clients were the Otis Steel Company and this is where she honed her skills of capturing people, their plight, and emotions. In her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, she reminisces about how the Otis security was reluctant to let her click. One reason was her gender – no one expected a graceful lady with her delicate apparatus to get into the rough heat, danger, and dirt of the steels mills of the 1920s. Her reputation grew for originality and in 1929, she was hired by the Fortune magazine. She was sent to Germany to photograph the Krupp Iron Works, one of the largest European companies of the 20th centuries that dealt with iron, steel, and ammunition. They were notorious for the poor working conditions back then. She went ahead alone to cover the First Five-Year Plan in the Soviet Union and eventually did photo-essays of the Dust Bowl as well. Dust Bowl was a severe dust storm in the American Midwest of the 1930s. These assignments helped her develop her dramatic style and focus on people instead of locations. Her compassion grew and her relationship with her subjects deepened. She covered the Second World War as a direct employee of the US armed forces. She went to North Africa and the ship she was due to read the continent on was torpedoed and sunk. Bourke-White survived and captured the everyday misery of the Allied infantrymen in the Italian campaign. She covered the siege of Mosoq and at the end of the war crossed the Rhine River (Germany). Her photographs of the emaciated inmates of concentration camps, bodies in the gas chambers and German survivors became the world’s window into post-war Germany.

Surprisingly, most other world-class photojournalists and even Indian photographers had little interest in what is now deemed as the greatest mass migration in the world.

She first took portraits of Mohandas Gandhi. Remember the one in which he is sitting with the charkha or the spinning wheel? That’s by her indeed. But of course, she was well aware of the historical fact that millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs are soon going to move from east to west in India.

The Indian Partition displaced nearly 15 million people on religious lines and the refugee crisis was riddled with violence, deaths, starvation, and rapes of an estimate of two million people. There are just a handful of images of the mass exodus available.

Her autobiography, the rediscovery of her private notes and companion Lee Eitingon’s notes reveal how Bourke-White conquered this feat. Bourke-White was courageous and the experience in the Second World War came in handy. Her companion Eitingon was also an experienced reporter.

Both of the women had been reminded of the dangers of reporting in an environment where native women were being “abducted”. Therefore, Bourke-White’s resourcefulness came in handy; the two journalists attained a Jeep and an escort of British soldiers.

Despite this, the danger was always lurking around. In Lahore, they encountered a truck full of refugees besieged by 30 men with spears. The soldier in their escort intervened with a gunshot before all of them escaped into the jeep.

Today, it is hard to imagine the partition because the times have changed so much. But we have Bourke-White’s black and white images of disease, starvation, bloodshed, helplessness, and grief during the partition. The caravans of refugees, on foot, bullock-carts, trucks, and trains – their faces and despair have been eternally preserved thanks to her courage.

South Asia as a whole obsesses over the history and politics of the partition of India. The human faces are the Jinnahs, Nehrus, Gandhis, and Mounthbattens. Until recently, little attention was paid to the millions of survivors who were ordinary people. Moreover, she gave a face to the women survivors who were strategically ignored or overlooked. Bourke-White gave these women and their suffering a face.

Later in her career, she covered the Korean War as well. She retired from the Life magazine in 1969 and died in 1971 after a difficult, Parkinson disease-ridden old age.

The writer is based in Lahore and tweets as @ammarawrites. Her work is available on www.ammaraahmad.com

Published in Daily Times, August 1st 2018.