The concept of self-determination is a vexing but significant topic in the field of human rights. It is the idea of government by the consent of the governed eternally memorialised in the soaring prose of Thomas Jefferson in America’s Declaration of Independence. Self-determination enjoys universal support and is celebrated in the United Nations Charter, in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and in the United Nations General Assembly resolutions.

Article I of the United Nations Charter enshrines it as a major purpose the development of friendly relations among nations based on respect for the “principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.” Self-determination was a central creed of President Woodrow Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points to end the World War I. Self-determination was also the libretto of India in obtaining independence from the Great Britain. A regards Kashmir, self-determination is expressly embraced in the United Nations Security Council resolutions as the international law formula for determining the status of a disputed territory.

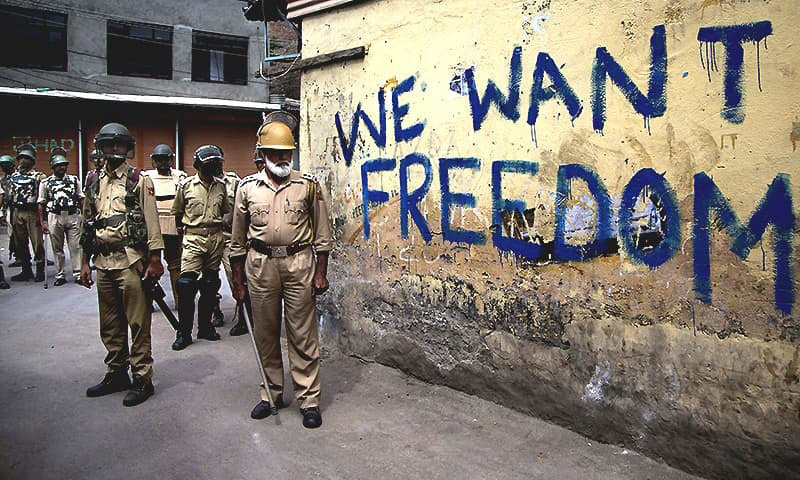

Kashmir’s legal and moral case for self-determination is equal or greater than that of the United States when it declared independence in 1776 with a population of three to four million. America’s grievances against King George III were but trifles compared to the human rights inferno that afflicts Kashmir. The Declaration of Independence protests the maintenance of standing armies, obstruction of beneficent laws, denial of trial by jury, and making the military superior to civil power. Kashmiris, in contrast, suffer from those same grievances, plus the gruesome human rights violations perpetrated by the Indian army.

Kashmir’s legal and moral case for self-determination is equal or greater than that of the United States when it declared independence in 1776 with a population of three to four million. America’s grievances against King George III were but trifles compared to the human rights inferno that afflicts Kashmir. The Declaration of Independence protests the maintenance of standing armies, obstruction of beneficent laws, denial of trial by jury, and making the military superior to civil power. Kashmiris, in contrast, suffer from those same grievances, plus the gruesome human rights violations perpetrated by the Indian army.

The people of Kashmir are resisting India’s iron-fisted military rule to vindicate their international law and fundamental collective human right to self-determination.

On that score, they are indistinguishable from Kosovar Albanians or East Timorese or Southern Sudanese, all of whom received international assistance to end their human rights suffering and to determine their own political destiny.

What is urgently needed is an assertion by Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Imran Khan of the necessity of taking new measures to effect the settlement of the dispute within a reasonable

time frame

Kashmir, a former princely state under the suzerainty of the British Raj, achieved independence on August 15, 1947, when Britain renounced its dominion over the territory. On that date, Kashmir had neither opted for accession to India nor accession to Pakistan, and was under no legal obligation to relinquish its independence. India did not then argue that Kashmir was indispensable for its national or economic security. Indeed, India championed a resolution in the United Nations Security Council in 1948 mandating a plebiscite in Kashmir conducted by the United Nations to determine its future sovereignty.

It is apparent from the record of the Security Council that India articulated the principle, accepted the practical shape the Security Council gave to it, and freely participated in negotiations regarding the modalities involved.

However, when developments inside the State of Jammu and Kashmir made her doubt her chances of winning the plebiscite, she changed her stand and pleaded that she was no longer bound by the agreement. Of course, she deployed ample arguments to justify the somersault. But even though the arguments were of a legal or quasi-legal nature, she rejected a reference to the International Court of Justice to pronounce on their merits. This is how the dispute became frozen with calamitous consequences for Kashmir most of all, with heavy cost for Pakistan, and with none too happy results for India itself.

The time for deception is gone. All that is needed is going back, yes, going back, to the point of agreement that historically existed beyond doubt between India and Pakistan, and jointly resolving to retrieve it with such modifications as are necessitated by the passage of time. That point of agreement is the one India as well as Pakistan, each independently, brought to the United Nations Security Council when the Kashmir dispute was first internationalised. In fact, the Security Council itself took that point as the basis of the resolutions it later formulated. The point was one of inescapable principle – that the future status of the State of Jammu and Kashmir shall be decided by the will of the people of the State as impartially ascertained in conditions free from coercion. The two elements of a peaceful settlement thus were, first, the demilitarisation of the state (i.e. withdrawal of the forces of both India and Pakistan), and a plebiscite supervised by the United Nations.

Now what is urgently needed is an assertion by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Prime Minister Imran Khan of the necessity of taking new measures to effect the settlement of the dispute within a reasonable time frame. To that end, India and Pakistan must together prepare a plan for the demilitarisation of the state with safeguards for security worked out together.

Confidence that a real peace process is being launched between India, Pakistan and the Kashmiri leadership would be inspired by the ending of repressive measures within the Indian-occupied area by both the federal and the state authorities. If sincerity is brought to the process in place of cheap trickery, a dawn of peace will glow as never before over the region of South Asia and beyond.

The writer is secretary general of the World Kashmir Awareness Forum