In July 2011, as an 18 year-old, like a hero, he defended 16 runs (going 6, wicket, 1, 0, 0, 0) with his left-arm spin in the Super Over of a final against Karachi Dolphins, to lead Rawalpindi Rams to a sensational title victory. He had taken three cheap wickets earlier in the match, in Karachi’s 20 overs. A year later, now 19, he was in the national team, a surprise package at the 2012 World T20. Against South Africa, he announced himself to the world, opening the bowling (and having Hashim Amla dropped by Kamran Akmal in that first over) and then bowling a maiden to Jacques Kallis in his next over. He would go on to play six more T20s and an ODI but in that period he was an undisputed prospect, the surefire next big thing for Pakistan.

In July 2011, as an 18 year-old, like a hero, he defended 16 runs (going 6, wicket, 1, 0, 0, 0) with his left-arm spin in the Super Over of a final against Karachi Dolphins, to lead Rawalpindi Rams to a sensational title victory. He had taken three cheap wickets earlier in the match, in Karachi’s 20 overs. A year later, now 19, he was in the national team, a surprise package at the 2012 World T20. Against South Africa, he announced himself to the world, opening the bowling (and having Hashim Amla dropped by Kamran Akmal in that first over) and then bowling a maiden to Jacques Kallis in his next over. He would go on to play six more T20s and an ODI but in that period he was an undisputed prospect, the surefire next big thing for Pakistan.

That same year, while playing in a domestic T20 game, he injured a disc in his spine, a potentially career-threatening injury. It forced him to miss a dream tour of India. But he returned, four months later, and as good as he had looked before the injury. It didn’t take long for him to storm back to national attention, with eight wickets at just 13.0 in the 2013-14 National T20 Cup. He was young, shrewd beyond his years, agile in the field, and with all prospects ahead of him over the age of 32. Ahead of him were Ajmal, and the left-arm spinning duo of Abdur Rehman and Zulfiqar Babar so this wasn’t going to be easy. He could easily have been history, yet another young prospect lost to a combination of injury and unfortunate timing.

He did eventually return to Pakistan’s limited-overs plans, playing another couple of T20s and an ODI ahead of the 2015 World Cup. He didn’t make the cut for the squad and then, that same year, his career and life would be irrevocably changed. During the Pentangular 50-over Cup in Karachi, he was taken for a dope test. He tested positive for a banned substance. He was asked to appear before an inquiry for an opportunity to defend himself. He didn’t and was banned for two years. Even before this there had been signs he was being reckless with his career and this time, it was done. It was over.

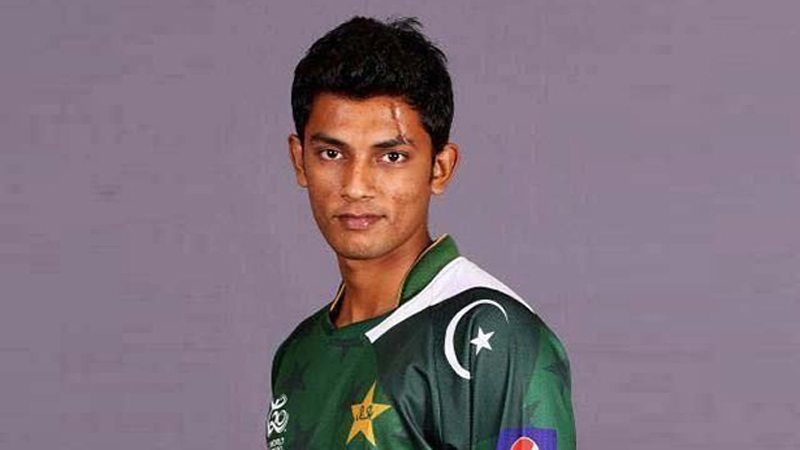

And then he all but disappeared down a black hole. Nobody knew where he was between 2015 and 2017. According to some reports he slumped back into a miserable existence between his hometown Sialkot and Lahore, moving with company that wasn’t right. His family was concerned. “He has no direction in life and he doesn’t listen to us,” his father, the man responsible for getting him into the game, away from kite-flying and snooker, once told ESPNcricinfo. He was still playing cricket but on the streets. He had no access to the lush green grounds maintained by the PCB. He wasn’t allowed to enter the National Cricket Academy (NCA). Everything cricket had given him, a social network and the sense of entitlement that comes with being an elite athlete, all of it was gone. This was Raza Hasan.

On Sunday, Raza Hasan was picked up by Lahore Qalandars for the third season of the Pakistan Super League (PSL).

One evening in May this year, Aaqib Javed, the former fast bowler, coach and now director of cricket operations with Lahore Qalandars, saw a hard-up looking boy standing just outside the NCA’s main entrance. “I saw this boy wearing dirty clothes and torn shoes, but there was still some mischief on his face,” Aaqib told ESPNcricinfo. “I stopped and realised it was Raza Hasan, a sensational prospect for Pakistan when I left for the UAE coaching job in 2012. “I called him over and asked, ‘What have you done with yourself?’ He had a lot of complaints about his life, whining about so many things. I picked him up and took him to our Lahore Qalander academy in Lahore.

“His ban was over by then but no one was accepting him back as he was in a terrible state, broken badly, and he required extensive rehabilitation which he could not afford to do on his own.” Hasan was born in Sialkot, a city with as rich a tradition of cricket as any in Pakistan. It is famed for its sporting goods industry of course, and cricket equipment is among the first toys a child gets. It isn’t a big city but it has a competitive club circuit so it isn’t easy to come through. The cricket fraternity is close-knit and the sporting goods industry is a major sponsor of players and local tournaments.

Over the years it has also become a steady supplier of talent to domestic and international cricket. Its T20 side, the Sialkot Stallions, were among the most successful T20 sides in the world, having won five consecutive T20 cups in Pakistan from 2006, during which time they had a winning streak of 25 consecutive games. Hasan grew up around this glory, around players like Shoaib Malik, Mansoor Amjad, Shahid Yousuf – all heroes of the city. But he was also one of the few to fall out of that fraternity, losing his entire support structure around him until Aaqib found him. He was in an especially bad way then, Aaqib suggesting that the positive dope test was not just a one-off but part of a longer, broader descent.

“The best thing when I found him was that his passion for cricket was still alive. But unfortunately he was struggling to find his way back and I blame the bad company he was keeping. He wants to revive himself but on his own terms and that wasn’t possible. I had a lengthy argument with him about this, but I have my own problem – I couldn’t resist myself by not helping. It was really tough because he was addicted to many bad things which he had to leave. He promised that he would but he wasn’t always honest about it. We spent a lot of money on his rehabilitation but on a few occasions he ditched us. I had to kick him out from our academy a few times to make him realise the importance of what we are doing for him. We had promised to help him revive his career and give him back what he lost over the years.”

At his peak, Hasan could have played for any domestic side though he ultimately remained loyal to National Bank of Pakistan (NBP). But after the positive test he lost his contract and so, the very first thing Aaqib did was to convince NBP to take him back. They did and are unlikely to be regretting it. He returned to first-class cricket this season by picking up 12 wickets against Faisalabad in his first match back – in the Quaid-e-Azam trophy so far, he has 32 wickets in 7 games with three five-fors. For now Hasan seems serious about his rehabilitation. According to Aaqib, he doesn’t even carry a mobile phone anymore, mainly because he wants to cut all links from his previous life. Aaqib will have his hands full because soon, through the PSL, Hasan will be firmly back in the limelight.

Published in Daily Times, November 16th 2017.